Things have felt a bit fragile recently. I am four weeks into a twelve month stint out in Melbourne, which, as the crow flies, is precisely 10,544.94 miles from my home. I’m not a stranger to spending extended periods of time in different countries - I’ve now lived in five of them, but none this far away, and none for this long. It’s making me all wistful.

Australia is like an uncanny valley version of the UK. You are surrounded by mostly familiar things and mostly familiar language, with maybe one element changed so as to feel unnerving and wrong: Weetabix becomes Weet-Bix; Burger King retains its logo but transmutes into Hungry Jacks. Flipflops are thongs. You also become acutely aware of the fact that nobody you have ever known or loved back home is going to be awake when you need them. Everything is subject to a temporal delay; I cannot simply text my parents when things feel difficult, and the buzz of my friends’ comings-and-goings on social media drop off one by one soon after I wake up. It’s lonely. I miss home. I am pushing people away who try to get to know me because they can’t be a replacement for my loved ones. I have begun to wonder whether a profound grief I have been lucky enough never to know feels like an intensification of this, like being thrown out into the ends of the earth where everyone around you is continuing as normal, and you know none of them, and none of them are aware that if they even brushed past you for a second you could break.

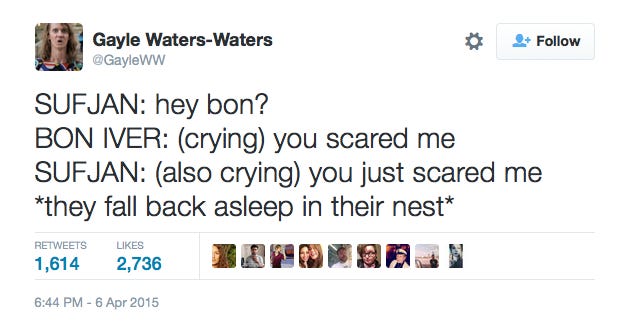

Two weeks ago, Sufjan Stevens released his latest album, Javelin. The lead single, ‘So You Are Tired,’ had come out a few weeks earlier, so it wasn’t an unexpected arrival. What was a surprise was the instagram post that accompanied the album drop: he had dedicated it to his partner Evans Richardson, who had, unbeknownst to us, died back in April. As an artist who is known for being intensely private, it was an emotional double blow, to see him open up about love and grief so that his art can fully honour the person who inspired it. Earlier this year, Sufjan revealed he had been diagnosed with Guillain-Barre Syndrome, and had subsequently lost the ability to walk. After what has ostensibly been his own personal annus horribilis, the widespread focus on the fact that this was the first time Sufjan had explicitly spoken about his sexuality outside of his music felt almost perverse. I have said before that I feel celebrities forfeit the right to be spoken about normally if their million-dollar income stream relies on the fanatical consumption of a constructed brand by ordinary people, but this feels different: he has not cultivated a God-versus-mere-mortal relationship with his listeners à la Taylor Swift, and I highly suspect that if the money and the adulation ran out tomorrow, he would carry on making music until the end of time. On his track ‘Video Game’ from his 2020 album, The Ascension, he gave us a refrain of ‘I don't wanna love you if won't receive it / I don't wanna save the world that way / I don't wanna be your personal Jesus / I don't wanna play your video game.’ He has experienced enough of his own personal strife without absorbing the sins and angst of the faceless masses, and as a devout Christian, merely the prospect must feel heretical. Even so, his testament to Evans felt like an appeal to the universality of love and mourning and the ephemeral nature of it all, and we should feel blessed that he bestowed it upon us.

But I don’t want to talk much more about Javelin. It is too tender right now, something I don’t want to touch while it is still newborn and delicate. It is a raw encapsulation of grief, and without being too presumptuous about a man I do not know on that level, I would imagine that Sufjan needs time to grow around it. What I do want to talk about is the equally devastating Carrie & Lowell, written in honour of his estranged mother Carrie, who died of bowel cancer.

I first started listening to Sufjan when I was 16, just after the release of Carrie & Lowell. This means that he has been a constant presence for a third of my life, but it feels difficult to remember a time where he wasn’t in it. I have to admit that even in those eight years, I haven’t listened to his entire discography - I haven’t even touched The BQE, or Enjoy Your Rabbit - for three reasons: firstly, that his music is finite, and I never want to get to a point where I cannot discover a new song for the first time; secondly, that I’m a creature of habit and always return to the things I know and love; thirdly, and most importantly, I truly believe that C&L is his magnum opus, closely rivalled by Illinois. There are a number of songs on other albums which, as individual pieces, I think could challenge some of those on C&L: ‘Futile Devices’ from Age of Adz, ‘The Predatory Wasp…,’ ‘John Wayne Gacy Jr,’ ‘Concerning the UFO Sighting…’ from Illinois, ‘Cimmerian Shade’ on A Beginner’s Mind, ‘Mercury’ on Planetarium, to name just a few. But as a cohesive unit, his 2015 work is a no-skip masterpiece that I have revisited again and again and again for nearly a decade.

well, i suppose a friend is a friend / and we all know how this will end

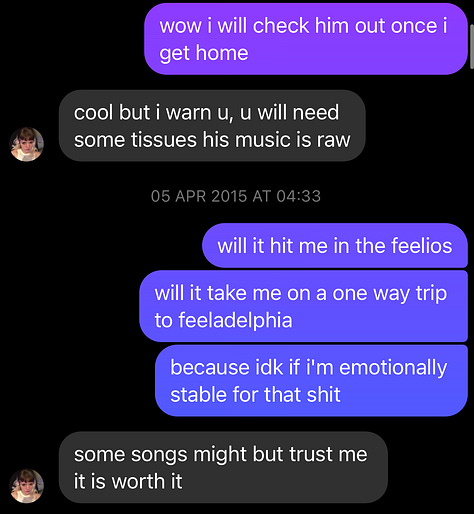

It was my friend Rhian who introduced me to Sufjan. Everyone has that one pal who is always ahead of the curve, whose artistic judgement they trust unquestioningly because the breadth and depth of the things they have watched and listened to and read is beyond anything they could imagine. Rhian is mine. I had been on holiday in Brighton with my parents, nursing a burgeoning crush on a boy I’d met online and trying not to think too hard about my upcoming GCSE exams. Rhian dropped me a message on Facebook messenger, telling me she thought I might like his music. I still have our conversation on my phone, and when I found it the messages made me laugh but also gave me a visceral pang of homesickness, not just because I am so far away but also because I miss a dialect we used to speak that has since become semi-extinct, a place my friends and I inhabited back then that we can never get back. I count myself lucky to have such long-standing friends, but we are all in our mid-twenties now, dispersed around the world; we present our growth and the developments in our lives to each other whenever we touch base, instead of being alongside each other and watching them happen concurrently.

My time in the classic rock Tumblr fandom circa 2012 instilled in me the value of listening to an album in order, so the first Sufjan song I ever listened to, ‘Death With Dignity,’ is the first on the album. It is also my favourite in his entire oeuvre, and has been ever since. I am not at all knowledgable enough to appraise music on a technical level - I took my ABRSM Grade 1 in Clarinet back in 2008 before giving it up because my teacher was terrifying and would leave notes like ‘LATE TO LESSON AGAIN! FOCUS!!!’ in my practice booklet, and I took guitar lessons for three years in secondary school, but that is the extent of my knowledge of musical theory. However, the way this song builds from light, progressive guitar fingerpicking to earthy piano interludes, from soaring vocals in ‘your apparition passes through me,’ to immediate whispers of the lower end of his vocal range in ‘in the willows, and five red hens / you’ll never see us again,’ all the while remaining so fresh and yet so fragile and tender it would burst into tears if you so much as touched it, is a remarkable feat. It’s a work of true dynamism in a way that many folk/indie/rock tracks could only hope to emulate, save for legends like Joni Mitchell and Kate Bush.

The second song I listened to was ‘Fourth of July.’ Widely regarded as one of the most depressing Sufjan tracks, it forms the exegetical seam for the rest of the album, describing the point of his mother’s death on which it all hinges. Carrie regularly abandoned her children as a result of experiencing numerous mental health problems over the course her life, including schizophrenia, bipolar and substance abuse issues, and Sufjan recalls having to be told by his aunt that she was in her final days. The song is dark but so devastatingly affectionate, a conversation alternating between Sufjan and Carrie where they refer to each other as ‘my little hawk / my little dove / my little loon’ and even ‘my little Versailles’ - a metaphor that feels particularly poignant considering Marie Antoinette had to abandon her palace home, leaving it empty and bereft of purpose.

Death always constitutes an ending, but it is one that changes us irrevocably, which always leads to a new beginning. For Sufjan, the grieving process led to this album, which he describes as ‘the first time in my life where I couldn’t sustain myself through my art. Maybe I had been manipulating my work over all these years – using it as a defense mechanism or a distraction. But I couldn’t do that any more, for some reason.’ In my own way, I was experiencing a turning point during this period of discovery where I had to be more honest with myself, too: being a bisexual teenage girl with a laundry list of unidentified conditions and neuroses was part of it, but on a broader level, I never quite knew how I was supposed to exist. It was in the long sprawling days where I went down to the Memorial with my friends; it was in the evenings where we sat in the field that they’ve fenced off now, shrieking Casimir Pulaski Day with Rhian and Eloise. Yes, it was then that I felt the shift. I existed there.

i’m light as a feather / i’m bright as the oregon breeze

I remember that winter being so crisp and full of light. It was the year I started sixth form; I received the album on vinyl for Christmas, and spent a number of days during the school break listening to it while lying on top of my duvet. I’ve inhabited that bedroom for sixteen years, permanently between the ages of nine and eighteen, and on and off since then. Now when I return, I feel I can breathe a little easier - I don’t go back so often now, but when I do, I find little pieces of myself in nooks and crannies and cupboards. School planners from year seven; exercise books I wrote fanfiction in when I was thirteen; university prospectuses I collected in sixth form, including one from SOAS where I’d dog-eared the pages for BA courses in Vietnamese and Georgian. I have a notebook where I have written a letter to myself every few years since the age of eleven. My mother practically begs me to clean out my room every time I’m at home, but to throw anything away would feel like consigning part of a narrative to a memorial void.

Back to December. The age-old ritual of lie down, get back up, flip the disk, lie back down, was probably the most movement I did in those two weeks. The inconvenience of it all was worth it to be able to hold the music in my hands, to see, physically, the tiny pops and scratches on the grooves, especially on ‘Should Have Known Better’ and ‘All of Me Wants All of You.’ On vinyl, the strumming in the introduction of the latter was so resonant I could close my eyes and feel it in the cavity of my chest. I went on to record a cover of it that I posted online, but I was conscious of the line ‘You checked your texts while I masturbated,’ especially as my parents and half of my extended family listened to my Soundcloud. Careful not to alienate my core fanbase, I managed to create a Kidz Bop version of the song by changing the lyrics to ‘You checked your texts while I sat and waited.’ I secretly felt very pleased with my own ingenuity.

Something I have struggled with in adulthood is the sense that I am growing out of the ability to choose my own path. In my adolescence, the choices were simply overwhelming, and so exciting I could combust: I could become a musician, or I could be an artist, or a writer, or I could put my all into academia, or I could do all of it somehow. I planned out my life to the letter. I could be anything, except mediocre. Now I’m 24 and work in recruitment, and I feel the opportunities turning their nose up and inching themselves away from me as if I am a carton of milk that is dangerously approaching its use-by date. I used to sing at weddings and compose songs, half-entertaining the idea that I could write and perform music as a career without really doing anything about it and, sensibly, putting my all into academia instead, because I wanted to be superlatively good at something that was somewhat quantifiable. Then I found out that beyond school it isn’t, and it’s not possible to be objectively the best at anything, and I could have dedicated my life to creating things without fear of being constrained by objective metrics of skill or talent. Then again, my vicious internal critic reminds me on a regular basis that ’Kate Bush was 13 when she wrote The Man With the Child in His Eyes. Laura Marling was 18 when she released her first album. Phoebe Bridgers was 23 when she made her debut. Your writing is uninspiring and you don’t pitch it anywhere except your silly little blog; you don’t have time to paint anymore and you’ve lost any sort of inherent ability to do so. It’s not going to happen.’ Am I allowed to do any of these things without being a child protégée?

I think this sort of existential angst, though, is precisely what Sufjan grapples with on ‘Should Have Known Better.’ Radical acceptance of our circumstances, despite the things we could have done, despite the paths we should have taken and the regrets we harbour over those we didn’t, is the only thing we can do to avoid a despair that will eventually destroy our ability to reason with ourselves. He implores us: ‘don’t back down, concentrate on seeing.’ Not doing so is to miss out on the majesty that is in front of us, in a world that is abundant with it. It is far easier to posture about this than to practise it. I’m not interested in mindfulness, and I would rather paper cut my eyelids than give my money to a mental health consultancy corporation selling me a meditation app, or sending me on a ‘digital detox course’ for ‘high-functioning empaths who are tired of capitalist and productivity-oriented notions of success,’ as if they aren’t the productivity-oriented capitalists in question. Cutting out the middle man and reminding myself that I do not have to be great - I only have to be good - is more powerful. The line ‘my brother had a daughter / the beauty that she brings, illumination’ gave me a funny feeling the first time I heard it - I didn’t know why, but I had a lump in my throat. Now I understand.

for my prayer has always been love

If I had a nickel for every time one of my favourite songs alluded to the Biblical story of Samson and Delilah, I would have two nickels - which isn’t a lot, but it’s weird that it happened twice. ’Drawn to the Blood’ by Sufjan and ‘Samson’ by Regina Spektor are like two parallel narratives, with the former taking the perspective of a third party who questions his faith in a God who allowed his lover to ‘[catch him] off guard’, and invokes Delilah to avenge him. The latter tells the tale of a Delilah who truly did love Samson despite her betrayal, changing the narrative to one where Samson loses his hair - and thus his strength - but his fate is reversed and his demise avoided through the redeeming power of love and devotion. Instead of Samson bringing down the columns of the building in which the Philistines had imprisoned him, he ‘goes back to bed,’ forgiving Delilah for the weakness she had engendered in him and choosing love and vulnerability over martyrdom and revenge. This is why, on the surface, ‘Samson’ feels like a narrative of human error and divine forgiveness that would not look out of place from a Christian musician. Interestingly enough, however, it is Sufjan who sings ‘What did I do to deserve this?’, and - perhaps even more interesting still - Regina Spektor is Jewish. While the scholarship is contentious, one of the proposed etymologies of the word Israel is rooted in the Genesis story where Jacob wrestles with an angel. God contends. Wrestling with God.

I think for anyone with only a rudimentary understanding of the two faiths, especially people who still think ‘Judeo-Christian values’ isn’t a completely redundant phrase, that there is an all too easy impulse to classify Christianity as The Forgiveness Religion (God is Nice), and Judaism as The Justice Religion (God is Mean). It’s understandable: so much of Judaism revolves around resistance and good triumphing over evil, and vast swathes of Jewish history are rooted in survival under intense and omnipresent persecution. Just like Jacob wrestling the angel, many Jewish people have openly questioned the motives of God since time immemorial, with one of the more recent and obvious examples being during the Holocaust. In Elie Wiesel’s La Nuit, there is an exchange between a character and the narrator, who have witnessed a brutal hanging of a Jewish child at Auschwitz-Birkenau:

‘Derrière moi, j'entendis le même homme demander: - Où donc est Dieu? Et je sentais en moi une voix qui lui répondait : - Où il est? Le voici - il est pendu ici, à cette potence.’

(Behind me, I heard the same man asking: ‘Where is God, then?’ And I felt a voice inside me, which answered: ‘Where is he? Here he is - he has been hanged here, on this gallows.’)

Having acknowledged his position as ‘the poster child for pain, loss and loneliness’, it is no wonder that the theme of questioning God, questioning himself, questioning love in all its forms, is a thread that runs through so much of Sufjan’s music, too. It is a curiosity that, despite describing himself as a ‘misanthrope,’ points to a deeper unwavering openness to humanity and to vulnerability, in the same way Regina Spektor’s Samson cedes his physical strength for the sake of emotional intimacy. After losing his own physical strength during his recent period of illness and allowing it to ‘renew his hope in humanity,’ the Samson comparison is all the more apt. In an interview for Uncut back in 2015, when asked whether ‘Drawn to the Blood’ was about his own abusive relationship, he simply answered ‘yes.’ His plea to the ‘God of Elijah,’ asking Delilah to ‘avenge [his] grief,’ is that of a wounded man whose faith in other people, in the divine, and in love itself is bruised but not broken: after all, ‘[his] prayer has always been love.’

When I was seventeen, after a three-month talking stage with a postgraduate student which ended unceremoniously, I wrote a song about it. I debated linking it here, but decided against it, because if you could bottle pure earnest teenage cringe and sell it, it would be a rich source. But despite an entire verse in terrible A-level French (I thought it was sophisticated) and all of the unadulterated yearning, there are parts of it I’m proud of - the chord progression and finger picking were based on Sufjan’s ‘No Shade in the Shadow of the Cross.’ To the man I was infatuated with, the short affair was probably nothing of note, something he no longer remembers in any detail at all. It was my whole world at the time. I was so fixated on the idea of finding God in someone else, someone who would be gentle with me despite their magnanimous presence, whom I could love so entirely that everything else fell to pieces. Gillian Rose once wrote that ‘There is no democracy in any love relation: only mercy,’ and I think, to a point, that it is true, but it is only half the story. The only thing I could conceptualise as romantic love was mercy from someone I saw as a deity. What I wanted was divine, earth-shattering devotion, a tyranny, a dictatorship: what I needed was a partnership of equals.

Sam and I have been together for six years now. I feel a love in my bones that is so solid it seems like it has always been there, waiting for the right time to materialise. It is a quiet love, something that has neither devastated me nor ruined my life; it is patient and kind and full of little mercies. He makes me laugh like a pig and rubs suncream on my skin because I hate the way it feels on my hands. I always thought the line ‘I love you more than the world can contain / in its lonely and ramshackle head,’ from ‘John My Beloved,’ was one of the most beautiful I had ever heard, but I remember listening to it again one day in 2017, after being together a few months, and feeling like I had been let in on a secret. I never realised how privileged I would be to show someone my snappy temper when I’m stressed, or my inability to get out of bed when I’m stuck in a rut, and not have to worry about whether they will still roll over the next morning and kiss me on the forehead because of - not in spite of - all of this. I know that he will.

Despite my amateur fascination with Biblical narratives, I’m always drawn to the least miraculous explanation for things. I heard someone describe this once as being ‘spiritually dead’; I prefer to see it more as a belief that everything either has a logical aetiology or is a happy coincidence. The Bible is one of the most fascinating narratological projects human beings have ever embarked on; providence and miracles are part of the personal mythologies we build around ourselves, and for me, that’s all there is to it. I don’t believe finding beauty in this is evidence of the Christian divine, and the portrayal of quiet, steady, reciprocated devotion in ‘John My Beloved’ is possibly something I will never understand on a religious level. But I have found it in a person.

shadows and light conspiring

If ‘Should Have Known Better’ and ‘All of Me’ are winter songs, ‘Eugene’ and the title track of the album mark a change of season: they are summer songs by the very nature of their imagery. They’re a childhood spent running through fountains and seeing the sun fragment into the entire spectrum of light through a million tiny droplets; they’re the colour green, with butter-yellow dapple rippling over it. They’re the moments where you are playing in the pool and suddenly you’re hit with your first ever realisation that you’re going to die one day and you’re not quite sure what this all means.

I was six when I realised my parents weren’t immortal. We had moved to Hamilton, twelve miles out of Glasgow, after my dad had been made redundant a couple of years before the financial crash. There was a cupboard under the bed in the flat we rented briefly that my brother and I used to squeeze into when we were playing hide and seek. In the darkness of it all, I remember suddenly thinking that one day, I wouldn’t enjoy doing this anymore. I wouldn’t be able to play: I would be too old. All of it would be pointless. I would be an adult, and I wouldn’t need my parents anymore, and they would die, and then I would die. I felt very morose for the rest of the day.

In a world where the nuclear family unit can be such fertile ground for abuse and maltreatment, I feel so lucky - and sometimes guilty - that I am blessed with the parents I have. I love the idea of ‘chosen family,’ especially in the context of queer communities who are all too often cut off from their loved ones, but I have the added privilege of knowing I would choose my own flesh and blood every time, in every universe. Hearing about the tenderness with which my dad took to fatherhood when I was born, seeing how endless my mother's love is as she nurtures the children she teaches, is enough sustain me a thousand lifetimes over.

It is no surprise, then, that I experienced such profound separation anxiety as a child. For some children, this is a response to profound trauma which manifests as attachment issues. For me, it was because it was the only place I felt safe. I was perpetually haunted by narratives where parents were abusive, absent or dead: once, when I was eight or nine, I decided to sort out my DVD collection by genre, and was perplexed when my parents came to see what I was doing and burst into hysterical laughter when they saw I had categorised Goodnight Mr Tom as ‘Mild Horror.’ Mild horror has become something of an inside joke to us now, a family meme if you will, but at the core of it I think it’s an accurate reflection of my greatest fear. In my nightmares I would see a young boy locked in a cupboard by his mother, the vomit-covered corpse of a baby sister in his arms.

These two tracks are Sufjan’s odes to family trips around Oregon. The album in its entirety feels like an indirect sequitur to the albums that comprised the first two instalments of his abandoned, semi-serious ’50 states’ project, Michigan and Illinois: immediately there is a nod to the state that passed the Death With Dignity Act in 1994. The title track refers, amongst other things, to the meadowlark (the Oregon state bird), the Covered Bridge, and the village of Cottage Grove, while ‘Eugene’ directly evokes the second largest city in the state. In amongst all of these geographical marvels and summery folk melodies, there are painfully sad, often violent allusions to his relationship with Carrie firmly nested in the lyrics - in the same Uncut interview mentioned above, the only question Sufjan refused to answer was whether the line ‘Erebus on my back / She breaks my arm,’ was about his mother. In ‘Eugene,’ he describes finding a parental figure in a man who doesn’t get his name right - possibly a priest, who pours ‘community water’ on his head - and feeling ‘lost in [his mother’s] sleeve’ for as long as he can remember. Contrasting curiously light, often major-key tunes with lyrics that break your heart by a thousand cuts is Sufjan’s signature. It really does feel like mild horror.

Part of what moves me about Sufjan’s music is that I am challenged to witness life experiences that are alien to me, and to try to understand, even if I don’t grasp them fully. My Oregon was Dorset and Brighton and the south coast, driving through the dapple-green forests and falling asleep in the car and knowing I would be carried to my bed when we got there. I cannot comprehend having to cherish what little time I get with a parent who is intermittently lucid or functioning, and even less wanting to avoid them, but through the forgiveness and the complex knotty feelings nestled within the metaphors, I can be there for those around me who do. I’m comforted somewhat by the fact that Lowell Brams, Sufjan’s stepfather, continues to maintain an active presence in his music beyond Carrie & Lowell. Together, they set up the Asthmatic Kitty label, and in 2020, they collaborated on an instrumental album. It is a testament to the fact that you can choose your family, whether you come together by blood, or circumstance, or a mix of the two.

in a veil of great disguises, how do i live with your ghost?

I never quite know how to talk about my final year of school. I feel like I revisit it a lot - possibly too much, for someone who is 24 years old - but in a way I feel as if I live in the spectre of that period of my life. When things are good and constant, it disappears into the background, a low thrum that is virtually imperceptible but still lingering; when things are bad or difficult or changing, I have nightmares about and begin to lose touch with its reality, the memory worn down by the number of times I pore over it. Even if I tiptoe around it, I feel it informs a lot of my writing, because what else can I do with it? Where else can it go?

I was seventeen when I met a man with whom I started an eight month tryst - I can’t call it a relationship, but I still consider him an ex of sorts, because of how intense it all was. In a matter of months I went from a child at 16 - inhibited, ungainly, naive and sheltered on my perilous journeys between my bed and the living room - to something else entirely at 17. I can feel my hands tensing up and hesitating even now, not sure how to put this on a page in a way that is respectful of a privacy that he and I are both entitled to, despite everything that happened, but that also teases out and excises some of my truth that I deserve to be able to tell. In any case, I was lonely and starving for romantic affection in a way that I think he, seeing my desperation, knew he could throw crumbs at to keep me alive while maintaining a hunger in me which left me so craven he couldn’t see me as human, and therefore he didn’t feel compelled to treat me as one. I spent much of the year on bus journeys to see him, my A-levels hanging in the balance, running from school to the bus stop fifteen minutes away in the pouring rain only to be cancelled on while on route. C&L was a welcome companion on the shameful walk back home.

Should I tear my heart out now?

Everything I feel returns to you somehow

I want to save you from your sorrow

Five months in, his sister died by suicide. She was sixteen. Without wanting to put myself at the centre of a tragedy where I was definitionally on the very edge, I found myself caught in the crosshairs of first love and first grief that, as a freshly turned 18 year old, I couldn’t contain. So I tried to be everything: lover, friend, mother, therapist, punching bag, moulding myself around his every need and self-immolating to provide him with some light. It’s a self-destruction that is captured so well in the two most devastating songs on the album, ’The Only Thing’, and ‘No Shade in the Shadow of the Cross’ - while Sufjan describes engaging in these behaviours to emulate, and thus find some intimacy, with his estranged late mother who could not show him the maternal care we all crave, I was punishing myself by trying to get into bed with a grief I could never understand, in hopes of receiving love in return. It is simultaneously the most selfless and most selfish thing I have ever done, to subject myself to a state of abjection out of love for another person, but at the root of it wanting something in exchange. The way he sings ‘There’s blood on that blade / fuck me, I’m falling apart’ destroyed me then, and still does now, six and a half years on.

I'll drive that stake through the center of my heart

Lonely vampire inhaling its fire

I’m chasing the dragon too far

once the myth has been told / the lens deforms it as lightning

Six years ago, an elementary school choir based in Staten Island uploaded this version of ‘Blue Bucket of Gold’ to their Youtube channel. Sufjan reposted it to his Tumblr shortly after. I come back to it occasionally, and I still can’t watch it without crying. Watching in real time as the children discover a sense of wonder and interconnectedness with the world through Sufjan, the way I did when I was 16 - it says more about the song, and about the man, than I could. The world is truly abundant.

Such beautiful wording