When things get difficult, I tend to dream about taking flight. I never have the courage to do it, but at the root of all my most ludicrous fantasies is the idea of being able to leave, to start afresh somewhere new and untainted by my inability to do anything right. Three years ago, in the midst of one of the worst periods of my life, I considered declining both offers I had received for Master’s courses I had wanted to do for years, and started Googling one-way flights to Bishkek. I don’t know what it is about the post-Soviet states that draw me in. Maybe it’s all the brutalism.

My mother always taught me the virtues of having an escape plan, even if it is purely a coping mechanism that you keep in your imagination to give yourself the illusion of choice. Nowhere do I feel more depressed than in places and situations where I feel like I have no way out. Often the prospect of freedom means I will stay, just to test my own endurance, just to give the benefit of the doubt and see if I can dig out any positives, deluding myself that I am there out of my own free will and that my sacrifice will mean something someday. One thing my parents didn’t teach me, however, is how to approach a fight or flight scenario and be able to fight without everything falling apart. There was never any conflict resolution, because there was never any conflict. My home life as a child was blissful, and now when I am faced with adversity, I dream of running. In reality, I mostly end up taking it. Some people see it as resilience. I know it’s learned helplessness, like a beaten dog.

I am having quite a turbulent time at the moment. I am not doing well in my job, which takes up a good 70% of my life and mental capacity currently, and I am very far from my family. I have just received a fully funded offer for a a PhD, which feels like something, at least. But I’m starting to get kind of existential about feeling as if whatever I do, nothing will ever make me truly happy. I’m not brave enough to blow up my own life, to destroy it only to make something beautiful, kintsugi-style, from the ruins. I’m not brave enough to book that flight to Bishkek or Almaty or even St Petersburg - even one with a return ticket - or to really fight back.

When I was in primary school, I dreamed of moving up to secondary, where the inane childishness that I felt was beneath me would miraculously dissolve. When I got to secondary, I became depressed and struggled with the social politics of it all, and I yearned for sixth form, where I was so sure I would love the element of choice over my studies. When I arrived in sixth form, the workload, the continuing curbs on my freedom, and my own loneliness made me act out in increasingly reckless ways: I kept a countdown for the moment I could start university, be myself, be loved, be free. I landed at university, relationship in full swing, and proceeded to have the most almighty nervous breakdown when I realised that nothing would ever change; there was something so empty and wrong about me, the luckiest girl in the world yet always wanting more, and wanting more still when she finally got it. Despite this, I held out my last hope for my year abroad in Paris and Cádiz, before it was promptly cancelled five months in by COVID. By this point, I had realised that this strategy of looking ahead to an idealised life for survival was all a lie, and now I can only think about the future with a visceral feeling of dread. That, and yearning for the years I wasted to yearning.

I’m writing this outside one of the many cafés by my office during my lunch break, one of the only opportunities I get where I’m not too tired, and where I can pretend that this is my full time job instead. The early afternoon sun is creeping higher into the sky. I can feel how paper-thin the ozone layer is here in the southern hemisphere, and the rays spill through the glass roof covering the patio and over my shoulder, light warmth until it intensifies to the point that I feel myself getting torched like a bug under a magnifying glass. My colleague, who spent time in the UK when he was younger, describes British sun as thin and watery and impotent, to the point that it made him depressed. But I find the sun here almost artificial, too good to be true, like cool-toned floodlights or banana flavouring or kitschy paintings of dogs playing poker. At least in the UK, there’s no pretence of warmth. Here it strikes you immediately, overwhelms you.

Kitsch, Milan Kundera notes, is the ‘absolute denial of shit.’ It is lowbrow; it is inane, and it is one of the mechanisms through which totalitarianism is able to operate. Tereza, one of two main female characters in The Unbearable Lightness of Being, is so psychically damaged by the vulgarity of living with her mother that she comes to reject anything that remotely resembles shit: having been forced by her mother to leave the door unlocked while going to the bathroom to desensitise her to shame and the fading beauty of the human body, she quite literally avoids looking at shit at all costs. She craves a beautiful life, one where she is fated to be with Tomas, who conversely embraces shit with abandon. Tomas’ lover, Sabina, is also a shit-acknowledger, an artist whose adverse childhood experiences pushed her the opposite way from Tereza: she declares war on the ugliness that kitsch represents. The narrator tells us to picture a scene of children frolicking in a field:

Kitsch causes two tears to flow in quick succession. The first tear says: How nice to see children running on the grass! The second tear says: How nice to be moved, together with all mankind, by children running on the grass!

It is the second tear that makes kitsch kitsch. The brotherhood of man on earth will be possible on a basis of kitsch.

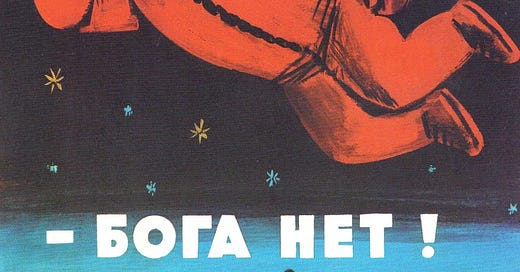

In The Unbearable Lightness of Being, Kundera often refers to kitsch in relation to the Soviet Union and its occupation of his home country, Czechoslovakia, though he describes it as ‘the aesthetic ideal of all politicians and all political parties and movements.’ Kitsch flattens all complexity, resists questioning and critique, clings to empty and baseless sentimentality and rejects reality or anything else it may deem unacceptable to its functioning. I first read the book just before leaving for Paris, and it quickly became my favourite of all time. Kitsch got lodged in my brain in a way I wasn’t prepared for. I began seeing kitsch everywhere: the UK, where everyone is either in denial of shit, or they revel in the shit and tell everyone it is good, actually; the trad and incel movements online, who believe their problems will simply melt away if we return to a culture where women function solely as decorative objects; the dark academia girlhood girlies like those I wrote about in my last post, whose attraction to notions of objective beauty supposedly precludes the fascist conclusions that it naturally leads to. I saw it in my peers, who posted the best of their year abroad foibles with captions about how it took them an international move to ‘find themselves.’ Most worryingly, I saw kitsch in myself, in my attachment to the new and the shiny and the strange and the impulse to fly away, based on zero evidence that this would actually improve my life in any meaningful way and despite being inordinately blessed with the life I have lived so far. Something I originally felt was simple idealism, simple daydreaming, suddenly took on this very sinister dimension. We were all in denial of shit. Is that better than being a cynical, miserable hag, the way I am now? ’The dictatorship of the heart reigns supreme,’ indeed. Until it doesn’t.

People have moved, and still do move, to Australia on the promise of a better life, better weather, better salaries. It is often called the Lucky Country for this reason. It is true that the weather is good here, the vistas are breathtaking and the opportunities are immense. But inscribed in every place name is a reminder that you are walking on an open wound: either a direct rip-off of somewhere in Britain, a crude bastardisation of a word in a First Nations language, or an homage to a settler whose Wikipedia page details some of the most heinous crimes against Indigenous people you have ever read. There is a high-profile femicide case virtually every other week, and domestic violence is rife. The separation of church and state is seemingly not a reality in practice and cultish fundamentalists permeate many aspects of public life. Donald Horne, who first coined the term ‘Lucky Country’ in his book of the same name, did so to be tongue in cheek, noting that Australia simply rides the coattails of its own luck - weather, resources, colonial dependence - rather than cultivating any real sense of cultural or industrial success. Of course, in 1964 when the book was written, misogyny and church domination were deeply entrenched, and there were still five years to go before New South Wales would dissolve the Aborigines Welfare Board - in other words, the first step towards ending the de-facto ongoing practice of removing First Nations children from their families and placing them in residential homes, with the aim of forcibly assimilating them into white culture. I doubt Horne had meant his critique as a damning indictment of Australian settler culture - quite the opposite, in fact, as ‘a comfortable believer in the British empire, comfortable about racial superiority’ in his early career. But the fact that the common usage of the phrase is so far removed from its context, based on a lie and on a mythology about Australia’s past and present, is kitsch in itself.

That’s not to say I haven’t found a lot of joy here, though. I love the animals; the sandwich shops are second to none, and the natural beauty here is surreal. Melbourne is a truly lovely place. But I always thought that moving out of the UK would provide me with a new lease of life. On the contrary, going back at Christmas and seeing my family and friends made me realise that I exist where the people who love me exist, and home is where the people who have always known me are. Maybe I have delusions of my own importance, but if I disappeared, I like to think that the four houses I inhabited in Coventry would feel the weight of the loss, like a phantom limb; I like to think that the paintings I left behind in the art rooms at my old school would instinctively know to stop waiting for me; that the bus stop in Leamington Spa, where I first felt my heart break, would breathe through the anguish all over again. If I disappeared, this place would never notice, let alone care.

I don’t know what sparked my abject revulsion to kitsch and earnest idealism, while never being able to let go of the prospect of the grass being greener elsewhere. I’ve been depressed on and off since I was thirteen; I find it difficult to express my feelings without couching them in irony (irony is the enemy of kitsch, and must be ‘banished’ to maintain it, according to Kundera). I love moaning about bad things and I hate popular ones, like Halloween and Friends, Sylvia Plath and Taylor Swift (I think I’ve said something scathing about her in the last three posts I’ve written). I was a nu-atheist for years and despised ‘organised religion,' because the saccharine sentimentality, blind optimism and resistance to interrogation specifically of Christianity rankled - to this day the only religion that remotely resonates with me is Judaism, precisely because God and his word can be an open question. It’s an embarrassingly childish, contrarian impulse to have, but I’ve always had it. I don’t do it to be cool - I’m not nonchalant enough about my haterism to be cool - I just seem to have an aversion to anything that comes to represent an uncomplicated universal good, any singular idea that comes to dominate or be presented as if it is above criticism. It might be a defence mechanism. You can’t have your illusions shattered if you don’t have any illusions in the first place. You can’t be seriously psychically, spiritually, morally injured if you never took yourself seriously to begin with.

Maybe the impulse has always been there, inside me, but the revulsion truly took hold when I had to drop everything and leave my beloved Cádiz before the border closed at the beginning of the pandemic. Before then, I was a dreamer. It is very hard to aspire to things when you feel old before your time and when we will probably all be underwater in thirty years. It feels like setting myself up for inevitable disappointment. But these days, I capture shards of dreams in the quiet, in the reminders that France and Spain and Italy will always be waiting for me; in the snippets of conversation in other languages I’m yet to learn; in the road trips through the Yarra Valley with Sam where I see solitary houses nestled amongst the vineyards, and I think I might want to stay there, out in the middle of nowhere, and write with no disturbance.

Maybe we are all in denial of shit. The British government, of the shit they subject us to, and the British people, of the the fact they live in a sewer but call it a kingdom. Australia, of its myriad problems dazzled by a permanent, blinding sun. Trads, of a mythological past that forms the foundations of their hate-filled aspirational future. Me, of the shit that an idealised future would involve, which would most likely resemble the shit I currently deal with in my life, but also of the shit that dominates the nihilist outlook that I cling to, and which resists all evidence that things might one day be worth it. There’s nothing more gauche than being stuck in the mindset of an angsty teenager despite being an adult, even if you are a particularly depressed adult. But I suppose life is and always has been all about these lies we tell ourselves to survive, these stories and fables and little religions. After all, as Kundera once said: ‘none among us is superman enough to escape kitsch completely. No matter how we scorn it, kitsch is an integral part of the human condition.’

love this. "Maybe we are all in denial of shit. The British government, of the shit they subject us to, and the British people, of the the fact they live in a sewer but call it a kingdom" made me shed a tear.

Easy refutation of this entire piece:

"Good things are good."

You will cuddle the puppies. You will delight in the pleasant scenery. You will be content in the anarchocommunist paradise.