you people can't do anything

Miserable teens, fascist nostalgia, and wellbeing as a weapon in the culture war: what is behind the rightward swing in mental health and disability discourse?

Have you heard? No one wants to hear about your mental health anymore, if they ever did. It’s passé. It’s cringe. It’s a sign of a cultural decay which you, the individual, are responsible for upholding. We can all un-diagnose ourselves and breathe a sigh of relief that the powers that be have decided it’s over.

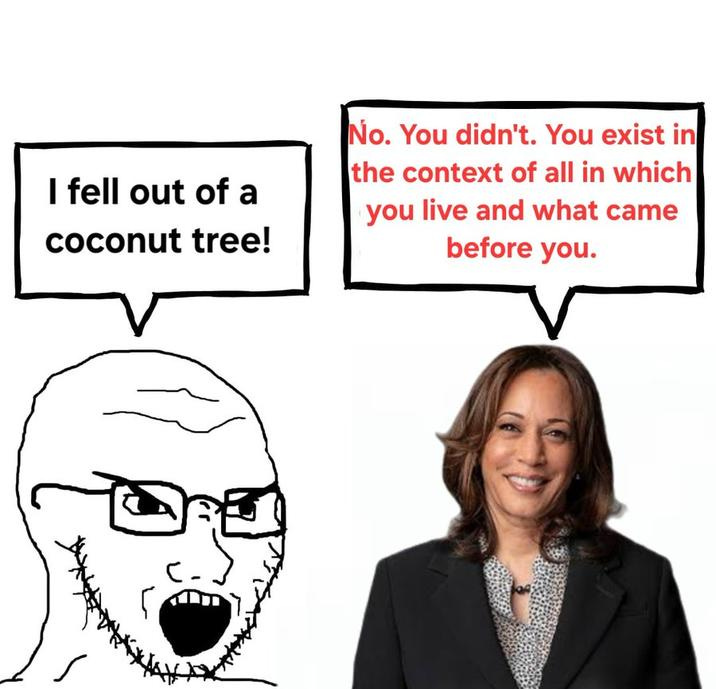

Everyone is tired of hearing about it, unless it can be used as a stick to beat you over the head with. It’s a relatively minor problem in the grand scheme of things, but at the moment it seems you cannot post a single thing online about the mundane realities of having ADHD without both the worst people on earth and those who would reasonably consider themselves progressive accusing you of ‘not being able to do anything,’ a viral meme that was only mildly funny the first hundred times I saw it weaponised against people making unserious throwaway comments about their condition. Mean-spirited mockery and tired accusations of being whiny and sensitive abound. But the other day I read this rather more serious article, and then this one, recommended by a number of middle-aged conservative rent-a-gobs who had wormed their way onto my Home page, about how young people are more mental than ever and lack resilience but are also over-reliant on therapy and anti-depressant medication to the point of chemical castration. I was confused: surely seeking treatment and talking openly about your issues is, by definition, a form of resilience. It is identifying a problem and attempting to resolve it. It is adapting to an obstacle that is put in your way and withstanding the hardship it brings. Life is difficult, and young people have not lived enough of it to grit their teeth and sail through without a few tears and tantrums and failures - this is just what it means to grow up.

But the confusion continues. Apparently, unless people suffer in silence, they are doing everything wrong, from rebounding after difficult experiences to relationships. Young people are supposedly more “sexless” (compared to what? Many of them are still literal children!) because they’re on SSRIs, because they’re depressed, because they’re on social media, which makes them depressed. We live in a society. We live in a culture. We live in a generation. At what point do we tumble off this roundabout of circular logic and say something of substance?

To be clear, I think the author of these articles generally means well, and her surface-level concerns are fair enough. But I also think she has become embroiled in ultimately meaningless culture war bullshit for clicks and praise from some of the cruellest people working for the most indefensible rags in the online mediasphere. She is not the only one. Dominique Taegon, formerly known as Dominique Samuels, became a well-known face on GB News before she had even reached her mid-twenties, before realising she had been made, in her words, ‘a cog in a rather sinister machine, designed to keep people in a perpetual state of either shock, anger or fear, packaged carefully as “news.”’ I get that it’s easy - appealing even - to write long, moral panic-driven screeds about how ‘we live in a society,’ (which one?), ‘we live in a culture,’ (what culture, and why is that?), ‘we live in a generation,’ (who’s we?) for an audience of natcon men in their 50s to slobber over, and referenced with shallow news coverage or agenda-driven stats that only tell half the story. National conservatives have slim pickings of token young mouthpieces to tout as their ‘voice of a generation,’ which is what has led to the likes of Sophie Corcoran and Kaitlyn Bennett becoming the oft-parodied fall girls for a movement that will use them as a rebuttal to allegations of misogyny and then sell them out at a moment’s notice if it suits them, after which they fade into obscurity and become known less as serious political commentators and more as girls who shat their pants at a frat party. Yes, they’ve earned money off their grift, which has encouraged them to grift harder, becoming more traditional, more radicalised - but they also become unserious, intellectually bankrupt caricatures of themselves. Is it worth it?

There is also a blatant appeal in remaining deliberately vague, because to say something of substance by directly identifying the root causes of a vast swathe our societal, cultural, generational ills would require us to think a bit harder about the material conditions that caused them, beyond ‘living in a generation.’ But these are often the same material conditions which aforementioned older conservative men have a direct stake in upholding. Right-wing populism thrives off making flimsy, chimerical scapegoats out of whatever seems most convenient - Gen Z, ‘victim mentality,’ phones, modernity, trans people, Jews, 15 minute cities - without ever being able to adequately articulate why they are the root of the issue, rather than forces that are bigger than any of them combined.

The problem with trying to chart generational problems is that the concept of a generation is on shaky ground from the start. Being born in 1999 would place me at the top end of Generation Z, alongside the 14 year olds to whom I taught GCSE French last year. What exactly do I have in common with these children? We weren’t even born in the same millennium! It has become such a widespread myth that in 2021, Phillip N. Cohen, a demographer, galvanised hundreds of other sociologists and social scientists to sign an open letter, followed by a Washington Post op-ed, denouncing the commonly pedalled delineations between age cohorts: ‘The division between “generations” is arbitrary and has no scientific basis. […] With the exception of the Baby Boom, which was a discrete demographic event, the other “generations” have been declared and named on an ad hoc basis without empirical or theoretical justification.’ Many of the quirks and unappealing traits attributed to “Gen Z” were once upon a time attributed to millennials, and to Gen X before them, such as selfishness, oversensitivity and a resistance to authority… all of which are just hallmarks of the turbulence of youth. Generation labels are effectively like astrology or MBTI for people who think they’re smarter than that. It turns out that across history, the one commonality that brings people of all ages together is hating young people and their behaviour while ignoring the intertwining social, economic and historical contexts that made them that way - contexts that their elders helped shape before they even existed.

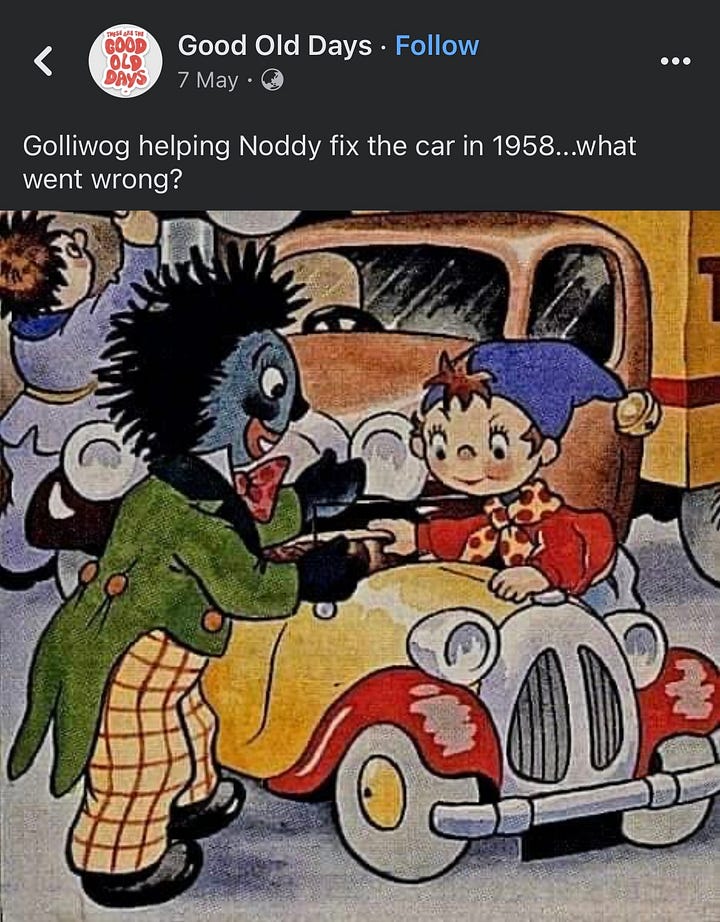

There is a much darker underbelly to this wholesale rejection of modernity and ugliness and the realities of mental illness, though. I wrote about the shadowy networks that link medical scepticism and the extreme right previously, and examining the appeal of kitsch for totalitarian political systems is something that continues to tighten its grip on me. We see a lot of this open totalitarian kitsch in online trad circles - I think it is best summarised in the million-follower Twitter account Culture Critic (@Culture_Crit), whose regular diatribes about the evil of brutalist architecture (ugly) vs the blessings of classical architecture (beautiful) act as an apt synecdoche for the entire phenomenon - but there is also an attraction to it for normal people who aren’t ordinarily hooked up to the online discourse mainframe. Nostalgia is, in many cases, the hook that draws people into far-right ideology, and forms the very irrational and unstable foundation of much of its propaganda.1 One example is what I like to call the Facebook Nostalgia to Far-Right Pipeline. In the context of the UK, this often involves older, not particularly technologically literate, usually more regional and socially conservative (but by no means politically committed or coherent) Facebook users joining online nostalgia groups or local area pages, called things like ‘MEMORY LANE UK,’ ‘RUGBY TOWN: THEN AND NOW’ or ‘PRIDE OF STOKE-ON-TRENT.’ Often the aim is to reminisce on the past or to learn more about the history of their local area. However, the comments on innocuous posts like ‘Whoooooo remembers proper bin men’ routinely descend into cries of “NOT LIKE THIS NOW. TOO MANY IMMIGRANTS AND SNOWFLAKES. WE USED TO SEND CHILDREN DOWN THE MINES.” The more people submerge themselves in this patriotic yesteryear circlejerk, the more radicalised they become, until their political outlook ends up as some variation of ‘REMEMBER GOLLYWOGS? NOW THEY’RE RACIST. BECAUSE OF WOKE.’ And sometimes, worse: ‘LOOK AT WHAT (((THEY’VE))) TAKEN FROM US. BTW I THINK ALL NON-WHITES SHOULD BE DEPORTED.’

Overseas, Samuel Merrill elucidates this phenomenon particularly well in Sweden, where far-right political organisations have mobilised on Facebook to create ‘enclaves within which overt or covert far-right discourses and the sorts of hate-speech underlying them can intensify, while simultaneously providing entry points to broader digitally networked audiences that allow the greater acceptance and normalisation of those same discourses.’2 These groups and the content in them can fly under the radar of decent people’s sensibilities by ‘creating digital noise, claiming plausible deniability, and transferring and distributing liability.’ In short, anyone is vulnerable, and the lack of accountability and internet literacy surrounding far-right dogwhistles allows it to spread through seemingly ‘reasonable’ or ‘moderate’ conservative rhetoric.

We talk a lot about the online far-right radicalisation of young men, but young women drawn into natcon and tradwife communities as well as the elderly are falling victim to an algorithm that helps solidify their subconscious rightward leanings into concrete fascist sentiment. People start off just asking questions or just wanting open debate, before using right-coded buzzwords like ‘family values’ and ‘Western civilisation,’ and finally descending into doing wink-wink-nudge-nudge allusions to the 14 words. There are thinly veiled accusations of degeneracy to be found about anything, from Marxism 'subverting' America (no doubt alluding to the antisemitic concept of ‘Cultural Marxism,’ which refers to the Frankfurt school of predominantly Jewish academics - the use of the word ‘subvert’ is also a big tell here), to transing and sexualising our children. This is ironic, considering that they themselves are the ones thinking a bit too excessively about their kids’ genitals, whether they are having sex, or whether they are going to enjoy having sex if they take SSRIs (while conveniently ignoring the fact that one of the very common symptoms of depression is low sex drive in the first place).

The attraction of an objective notion of beautiful vs ugly, classic vs modern, and this directly mapping onto good vs evil, is that it is a simple thread to follow: binary, uncomplicated, no grey areas. People who are happy are beautiful and therefore good. People who are miserable are ugly and unapproachable and have a “victim mindset” because they can’t accept that it is all their own fault, and therefore they are bad. People who are happy must be strong and living virtuous lives full of beauty and tradition. People who are not must therefore be weak and moral failures. This framework of logic makes the people who believe it feel some form of control over their lives, like they are the chosen ones. But it is entirely illusory.

It is also straight out of the playbook of the Nazis themselves. Sander L. Gilman’s illuminating monograph, The Jew’s Body, details how Jewish men were conceptualised in the Nazi imaginary as effeminate and inherently sickly, their women as ugly harpies, both hysterical and prone to whining.3 The very word ‘hysteria’ comes from the same root as the word ‘hysterectomy,’ in that excessive, pathological emotion was the domain of women. To codify it as an inherent trait not only of Jewish women, but of Jewish men, is to dehumanise both entirely. Then and indeed now, Nazis regard their communities and cultures as hotbeds of degeneracy, full of individuals who have always lacked strength and resilience and beauty, and who deliberately exaggerate their constant cycles of persecution due to their victim mindset.

This is part of the reason why if you even lightly scratch the surface of so many of these appeals to tradition, physical and mental strength, and aesthetics, you will find barely concealed fascist dogwhistles. Georges Perec elucidates this most interestingly in his semi-autobiographical text, W, ou Le souvenir d’enfance - a survivor of the Nazi occupation of Paris whose parents were deported to the camps, the second half of the text takes place on a fictional remote island named W.4 It is supposedly a slickly-run paradise, with functioning governance and utilitarian ethics, whose fit, disciplined inhabitants are primed to compete in the Olympics and are obsessed with the pursuit of victory: a utopia, for all intents and purposes. However, we realise this obsession with victorious athleticism is because it is the only way to guarantee their survival; the athletes are beaten or killed if they fail, rewarded with women to reproduce with if they don’t, and the island is revealed to be a concentration camp. Walter Benjamin wrote a good forty years earlier that ‘[Mankind’s] self-alienation [under fascism] has reached such a degree that it can experience its own destruction as an aesthetic pleasure of the first order.’5 The cult of beauty, of ‘rendering politics aesthetic,’ of identifying certain works of art as ‘degenerate’ while glorifying war and domination and suffering as a ‘flowering meadow with the fiery orchids of machine guns,’ is always necessarily cannibalistic. The disempowered and vulnerable always bear the brunt.

So, why are young people so miserable? Anyone pointing to one singular cause is likely trying to sell you something, be it an ideology, a political agenda, or a product (subscribe to my podcast! Buy my book! Take my supplements!). But if I were to hazard an answer that I think comes closest, I would say that it is everything and also nothing: teenagers and young people have always been miserable and insecure and wanting to cling desperately onto anything that provides a sense of stable identity, whether it manifests in TikTok addiction and labelling themselves demisexual, grunge music, or the juvenile delinquency of the punks and hippies. You only have to read the first few pages of Joan Didion’s ‘Slouching Towards Bethlehem’ from her infamous compilation of the same name to see this in evidence: teens running from home, dropping acid in San Francisco communes and getting hooked on speed in the process, evading the police, escaping their ‘all-American bitch’ mothers and chasing the high of something more, more, more.6 On a more gendered level, young women weren’t happier or more fulfilled when kept inside as housewives or animate uteruses: many of them were out of their minds on barbiturates or even lobotomised. Is social media addiction or delayed adulthood really so much worse than this? Posturing like all of this misery is new and a sign of something being uniquely wrong with kids today is laughable. Different, yes - novel, not at all.

The specific difficulties of the current moment only exacerbate this, however, in a way we are still yet to get to grips with. We are three years out of a pandemic where children saw their family members risk their lives and die; a lack of free third spaces means children and young people’s major mode of contact is online; they watch as their parents struggle to withstand the cost of living, or battle precarious situations themselves upon moving out. Many of the children I taught last year back in the UK were objectively, not relatively, poor, and mental illness and poorly managed neurodevelopmental conditions were rife due to the lack of access to adequate mechanisms of support. Waiting lists for CAMHS and psychiatric services are approaching five years in some cases. It takes 20 weeks at the very least to be assessed for ECHP funding, which, if approved, provides schools with extra resources to help children in need to access learning to the same standard of their peers. Teachers were using food banks. State benefits are nigh on impossible to obtain without lengthy appeals processes. The Conservatives have just renewed their commitment to the Pension Triple Lock and pledged to establish mandatory national service should they be re-elected in July (while it is estimated that we are the first age cohort since the 1930s to earn less than our parents), bringing us to the point where even loyal Conservative pundits are floating the idea that the best way to be young and from the UK is to emigrate. What is the point of it all for young people when we are continually and egregiously shafted and then blamed for it? At what point does this end? At what point do we stop building on rotten foundations?

It is all very well referring a child to the school counsellor when they are living in a hotel because they are functionally homeless, or running wellbeing sessions for staff when they can’t afford to keep their heating on. There is only so much powerlessness, so much indignity in the mounting pressure that people can tolerate, and God, family values, or appeals to a mythical utopian past quite frankly are not going to change a single concrete thing for them. Resorting to the dopamine rush of endless scrolling, or to the sticking-plaster medical intervention of SSRIs, is not a cop out or a lack of resilience on the part of the individual - it is evidence of an abdication of duty from those who have the political and institutional responsibility to do something. It is not needless decadence or moral failing. It is a cry for help. Framing phones, or medication, or the rejection of tradition writ large as the root of the problem instead of the symptoms of it is a coward’s way out of confronting an ugly reality. The material conditions of free market capitalism have failed time and again to allow the most vulnerable people to live a dignified, comfortable life, and as these conditions worsen, so will the number of vulnerable people.

The recent discursive shift from empty platitudes about mental health, to the open contempt for people with mental illness and neurodevelopmental conditions more commonly seen pre-2010s, feels reflective of a massive swing to the right in general. But conservatives don’t want us on SSRIs, don’t want us in therapy (it’s woke, apparently), and don’t want any sort of concrete or meaningful change which would improve our lives, such as reducing housing and sustenance costs, better pay, and stringent labour laws to stop us working ourselves into an early grave - and no, banning phones or social media for under 18s as a policy proposal doesn’t count. Corporations pay us lip service, but only so they can extract more of our labour. On the other end of the spectrum, people who posture as left-wing, sympathetic and compassionate post viral memes about how people with ADHD are annoying and infantile, and rehash early noughties moral panic about how Adderall is overprescribed legal meth based on pseudoscience and vibes but presented as gospel, just to set themselves apart from the normies whose psychiatric diagnoses have skyrocketed in recent years. I can’t help feeling like the subtext regardless of political alignment is that if we can’t pull ourselves up by our bootstraps or treat our disabilities in a way that is inoffensive and expedient to them, it would just be more appealing all round if we didn’t exist. They simply want us weaklings dead.

In her brilliant analysis of the internet’s recent fixation on polyamory, Brandy Jensen came out with this little sparkling gem: ‘Too often these days I find myself in the position of defending someone I think is annoying from someone I know is dangerous.’ Teenagers and young people are often annoying. I am often annoying. Life is hard and people struggle and their struggles often sound negative and annoying. But I would much rather extend grace and understanding and kindness to people I find annoying than get into bed with people who would happily put our heads on spikes for being degenerates, simply because it scratches a satisfying itch to see them taken down a peg. I refuse to stand and listen any longer as people who revel in cruelty and misplaced righteousness deign to dish out smug moral lectures about ‘resilience’ and ‘victim mindset,’ especially to people whose entire existences rely on continual fortitude in the face of relentless persecution and hardship. Have some fucking shame. You wouldn’t last a second out there.

Barnes, David, ‘Going Back Somewhere: Nostalgia and the Radical Right’, openDemocracy <https://www.opendemocracy.net/en/countering-radical-right/going-back-somewhere-nostalgia-and-radical-right/> [accessed 28 May 2024]

Merrill, Samuel, ‘Sweden Then vs. Sweden Now: The Memetic Normalisation of Far-Right Nostalgia’, First Monday, 25.6 (2020), doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.5210/fm.v25i6.10552

Gilman, Sander, The Jew’s Body, 1st edition (Routledge, 1992)

Perec, Georges, W ou Le souvenir d’enfance (Gallimard, 1975)

Benjamin, Walter, The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction, 1936 <https://www.marxists.org/reference/subject/philosophy/works/ge/benjamin.htm> [accessed 28 May 2024]

Didion, Joan, Slouching Towards Bethlehem (4th Estate GB, 2017)

So well written. I’m really disturbed by Freya India’s writing because at face value it’s almost innocuous. Like it’s framed so similarly to the girlhood essays we see on here yet her work panders moral panic and individual failure. Thank you for putting to words what I’ve been struggling with for months.

thank you for writing this!! I’ve had such a similar piece in my drafts for months and have felt so weird about the lack of pushback FI has been getting. It’s all so insidious and unsettling…