all things change in the blink of an eye

Moving to London, springtime infatuation, and literally doing whatever you want

Everyone who moves to a new city, a bigger city, believes it will change them, and the vast majority of those supposedly anticipate it will be for the better. Why else would they go? Moving to Melbourne made me markedly worse: as a friend, as a daughter, as a functioning person. I began to rot from the inside, starting with my constant stomach issues and my terrible brain, before the badness seeped through to my skin and scalp, where it became dry and inflamed and my hair fell out at a rate I’ve never seen before. I became wracked with a social anxiety and a suicidal lethargy that has mostly gone away now. My winter started in April last year and didn’t abate until last week, as I left the southern hemisphere in September just as the temperature was beginning to turn, and I am now quite severely deficient in Vitamin D as a result. As

, a long time mutual of mine who is now more widely known as ‘the guy who lives in Ulaanbaatar Mongolia,’ says in his piece on his current home: ‘I don’t think I’m meant to be here. I feel, not homesickness, but the intense desire to make my life back home. […] My return feels prodigious, I can’t miss it.’ I had this same sense that my own personal world had stopped turning on its axis and would not continue until I got back: how could I not feel this way, when the only reason I was down in the Antipodes was for someone else? The minute I watched us cross over into UK airspace, I felt my jaw unclench, the knot between my shoulders unfurl slightly.Then my life fell apart, and I met someone who changed me, and I spent five months living back home with my parents, who I love but in whose house I reverted back to various versions of my teenage self. I was fourteen and fifteen and seventeen all at once, all ages I hated and enjoyed in almost equal measure and where I was self-possessed enough to know what I wanted but not old enough to act on any of it. I felt something shift when I turned twenty-six in our usual family holiday spot and one of my favourite places on earth, in Brighton, where we have spent a week virtually every year since I was eight. It was about three degrees but sunny and my brain felt as if it had been lifted out of my skull, refreshingly doused in cold water and put back in perfectly. The final step to hauling myself out of this slump was moving to London, which I did last week.

I’m now living with my two best friends from university for three and a half months, now that a room is available in their house. They are two of my favourite people I have ever met, and it is this that puts into perspective what a terrible friend I’ve been. Something in me — probably the feeling that my whole being had been corrupted like a computer file immediately upon leaving the country — had convinced me that all of my friends were dead sick of me, until the break up happened and the first person I called, scream-sobbing down the road the whole way to the station, was my best friend since I was eleven; until my two housemates-to-be FaceTimed me two days after it happened and immediately set up a dinner date for us at Roti King by Euston Station the next day. I could only eat two bites of an admittedly delicious nasi goreng and then cried the whole train journey back. But it meant the world to me.

London is something I had just accepted I would never be able to afford to do, despite wanting it more than anything. As a pre-teen, my best friend and I decided we would one day apply to Imperial College together, me for Medicine, her for Molecular Biology. Then my dad presented me with a rough breakdown of how much that would cost in actuality — the Conservative-Lib Dem coalition had just announced the rise in tuition fees from £3,000 per year to over £9,000, and even then, the cost of living in London was far beyond anything we could afford — and we realised that we were actually both more geared towards the humanities, anyway. So I had a triumphant moment when I dragged my suitcase through Euston, a sort of rite of passage I’m sure every provincial rube like myself experiences when they migrate to the capital, where I realised I had won. For the sorts of people I was surrounded with at university, London felt like a natural conclusion to three or four years on campus. But I knew I would never hold down a corporate job, would never do anything with a salary high enough to pay my rent, and mostly that my ex would balk at the idea. The stars just so happened to align perfectly for me at this moment, and I decided not to ignore it. I am trying to say yes to everything.

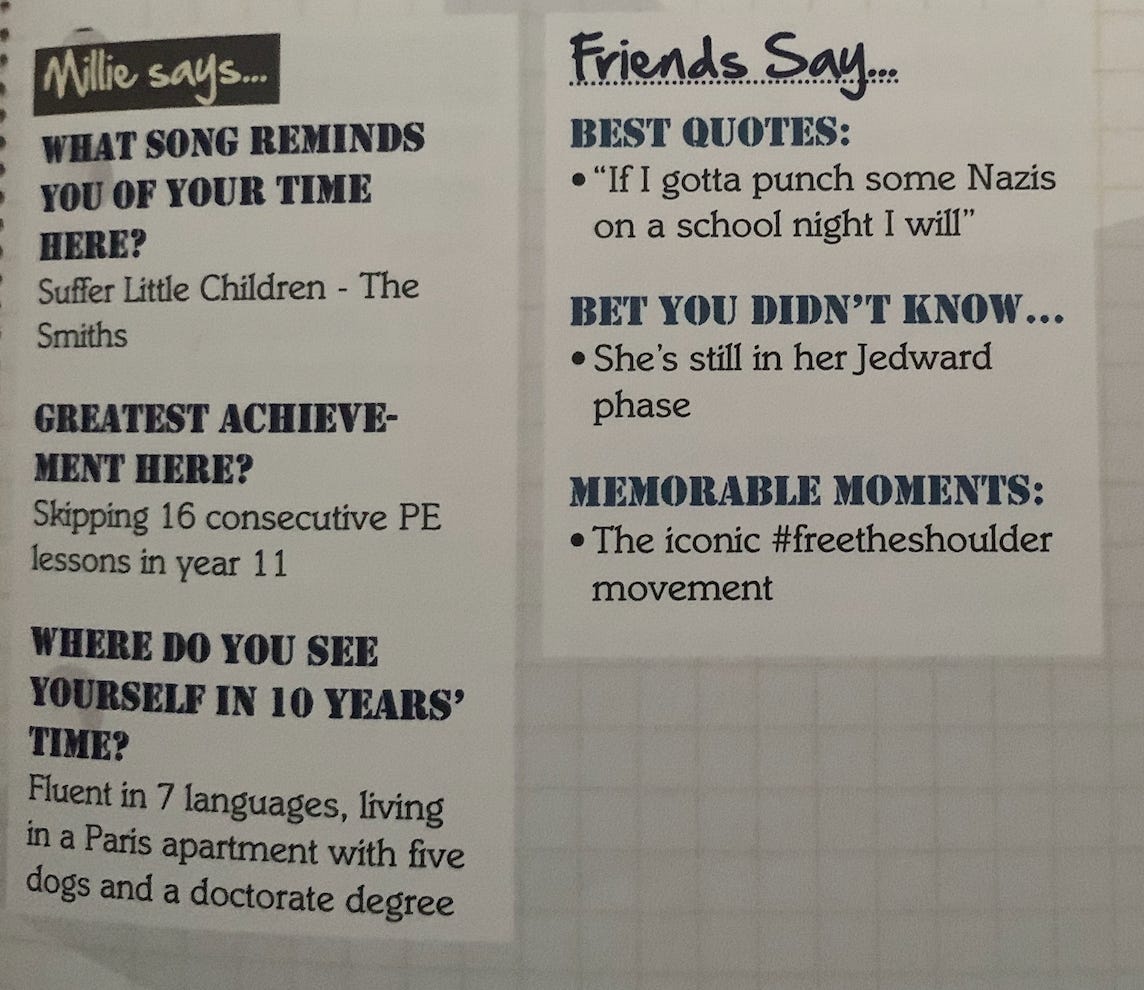

I am going back to the southern hemisphere, though. It was finally time to do something, instead of wallowing in my own inertia and indecision, resenting myself for it, and then wallowing in the resentment, rinse, repeat. So I decided to throw caution to the wind and book a trip to China. I used to study Mandarin at school, which I have written about here, and I always assumed I would go there at some point before my language skills atrophied too much. It wasn’t to be. There are so many things I wanted to do, just for me, that I haven’t done. I feel a lot of shame about it. People wiser than me have rightly pointed out that living as a servant to your teenage self’s hypothetical opinion of you is futile — why would you court the approval of a mentally ill seventeen-year-old? — but my tastes and interests and aspirations haven’t drastically changed since then, so she is a pretty good bellwether for when I veer off course, which I did over the last nine years. In my school yearbook, where it asked the question ‘Where do you see yourself in ten years?’, I responded ‘Fluent in seven languages, living in Paris with five dogs and a doctorate degree.’ It was tongue-in-cheek and deliberately exaggerated, but the exaggeration was the anchor that kept me wedded to this vision of myself and the world for so long: I would aim for the stars, but I could absolutely settle for competency in four languages, two dogs, an Oxford master’s, living in a big city where things happened, believing deep in my core that this would fill my cup. When I achieved all of this (though the dogs were technically not mine) upon moving to Melbourne and still wasn’t entirely happy, I knew that something had gone awry. It wasn’t enough. Nothing I did was for my own benefit. I was staying in a country far from nearly everyone I had ever loved in a job where I was being harassed for months on end and where I had nothing to gain from being there, but I also had nowhere else to go. I had lived this way for so long without realising that it had become learned helplessness, an acceptance that I had no other choice but this, while all of my many possible options lay inches from me on the other side of a one-way mirror.

I’ve been reading Julia Kristeva as part of my PhD research. I passed my upgrade, by the way, which means two things: one, that I am now officially a PhD student and no longer on probation, and two, that I completed what my examiner described as ‘one of the best pieces of first year work she had read’ at one of the lowest points of my life. I don’t mean to brag, but it feels like I have lost about forty percent of my cognitive capacity since last year, and I was certain I would have to revise and resubmit my work. I don’t have much else to be proud of lately. Anyway, Marta-Laura Cenedese made an interesting link between Kristeva and abjection and Irène Némirovsky and her fate as a Jewish writer who wrote antisemitic screeds for fascist newspapers before and even during the war, but nevertheless ended up wearing the gold star and ultimately perishing in Auschwitz.1 The debate about whether Némirovsky was a ‘self-hating Jew’ has been litigated and re-litigated for decades now. Kristeva describes abjection as ‘immoral, sinister, scheming, and shady: a terror that dissembles, a hatred that smiles, a passion that uses the body for barter instead of inflaming it, a debtor who sells you up, a friend who stabs you.’2 Much of this was true for Némirovsky: she once found a supporter and admirer in Robert Brasillach, editor of fascist newspaper Je suis partout, before he published an op-ed endorsing stripping French Jews of their citizenship.3 But what Cenedese alludes to is a sort of fatalism over the inability of foreign-born Jews to integrate in France that haunts her, and to Kristeva, abjection can also constitute a betrayal of the self, ‘something rejected from which one does not part, from which one does not protect oneself as from an object.’4 It is the fatalism of a beaten dog, an inevitability of suffering, because it is all you have come to expect. I had to take a break and stop reading at this part.

I still haven’t reached the point, as China is not entirely in the southern hemisphere. I will begin in Beijing, spending a few days by myself in the big city to get acculturated before my tour starts. I have always wanted to visit Beijing, especially because my teacher was from the north and the variety of Mandarin she taught us was the one they speak there, and I have a habit of tagging ‘er’ on the end of some of my sentences in a shoddy mimicry of her. Then I’ll join my tour group and we’ll take a sleeper train down to Xi’an to see the Terracotta Warriors, before heading to Chengdu on a bullet train. Before I got my A-level results, I always said that if I didn’t get into university, my backup plan was to get a job at the Chengdu panda sanctuary, as if they would hire me on blind enthusiasm and semi-fluent Mandarin skills alone. After a few days there, we will go south to Yangshuo where we will do a cycle tour of the rice paddies, before ending up in Hong Kong. Then I am flying to Auckland and will spend a week staying in the Waikato countryside, because I am hopeless, impulsive, and honestly quite besotted.

My friends and family are all excited for me, but curiously so. In any other circumstance they probably would have been warning me about the impact of my decisions, which will be significant both financially and emotionally. But after the year I have had, there is a sense that I have nothing to lose: they are finally seeing something from me that I haven’t shown them in a very long time, which is raucous, riotous happiness, if only for the moment. There is something in this that I have never quite experienced previously. The forbidden longing because I know it would never work in any serious capacity, the desire I feel despite myself — I have never wanted a person in this specific way before. The novelty and the impossibility of it all only intensifies it. I have always felt that springtime is the best time to feel like this, full of potential and novelty. Since booking the flight, I have been walking on air, wishing strangers a good day, smiling at every baby or dog I see. I quite like the person I am in the process of becoming.

I’m sat on a patio, transfixed by a bumblebee plundering a shrub full of lilac blooms for pollen. I had forgotten how fascinating it is to watch them. I’m trying a rose matcha for the first time and I feel a sort of kinship with him, drinking flowers. There is an awe about mundane things that are actually quite incredible which I lost when I turned nine or ten but came back to me as an adult, and another layer of gratification from simple pleasures that left my body over the course of the last ten months of back-to-back winters and unrelenting seasonal depression which seems to be returning now. The bee inspects each flower compulsively, like he is driven by a motor, barely stopping to breathe. I think if I had existed like this for the last few months, the way I am doing now, I may have gotten through it all with less heartache. I sit outside a café in the Spring sunshine with my new housemate and read, and we realise we are both on page 83, me of Némirovsky’s David Golder, her of Madonna in a Fur Coat. She reads me the line: ‘After spending two hours with a book, and finding it more pleasurable than two years of real life, I’d remember again that life had no meaning, and sink back into despair,’ and we laugh. When I get home, though, I realise this part is is followed by the sentence ‘I’d lived more during the past two weeks than in all the years of my life put together.’ I see friends and ride the night bus home and don’t feel guilty about getting back so late into the night. I’m not anticipating an admonishment or an eye roll when I arrive home, only the soft quiet of burying myself in my new bedsheets, and a message from someone for whom it is now tomorrow afternoon: always something funny and gentle and unserious, always offered up to me like pebble from a penguin.

Marta-Laura Cenedese, Irène Némirovsky’s Russian Influences: Tolstoy, Dostoevsky and Chekhov (Springer Nature, 2020), p. 17.

Julia Kristeva, Powers of Horror: An Essay on Abjection (Columbia University Press, 2024), p. 4.

Susan Rubin Suleiman, Irene Nemirovsky and the ‘Jewish Question’ in Interwar France (Yale University Press, 2012) <http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:10504663>, p. 8.

Kristeva, p. 4.

this was lovely to read. please write about your time in China!

congrats on a new chapter of your life!