cn: eating disorders, weight, BMI, vomit

I used to be vegetarian, a fairly long time ago now. At least it feels like it. I was concerned about the environment, and felt a lump in my throat thinking about the animals. Other than a brief flirtation with some chicken salad three weeks in, I was strict about it for two years, then pescatarian for another two, after having some pretty abysmal blood results which somewhat explained the previous nine months of on-again-off-again chest infections. Spiritually, I still identify with vegetarianism, and an involuntary reflex in me always goes to speak up whenever I get asked if I have any dietary requirements. The thing that ended it all for good is that my partner is an incredible cook. He spent lockdown gradually trying to wean me back onto meats: rosemary-studded lamb from the slow cooker; Nigella’s forty-garlic-clove chicken; sticky hoisin duck baos which feel like they could glue your tongue to the roof of your mouth. Beef bourguignon. Confit duck leg. Haute cuisine. We save up our money and splurge on food, because there are so many horrors in this life that it would be criminal not to enjoy such fleeting pleasures.

Eating, according to Kathryn Robson in reference to Sarah Kofman’s Rue Ordener, Rue Labat,

simultaneously marks a difference between what is inside the body and what is outside and breaks down that distinction; it points to a distinction between self and other even as it entails bringing the other into the self.1

The idea of food inhabiting not only the foundation layer of Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs but permeating throughout, up to the pinnacle of self-actualisation, is something I think will always fascinate me. I wrote about Kofman’s autobiographical work for my undergraduate dissertation - it’s a slim volume at only about 100 pages long, published just before her suicide in 1994, and details her experience as a child during the Nazi Occupation of Paris after her father, a rabbi, was deported to Auschwitz. Forced to go into hiding, she is separated from her mother and sheltered by an elderly French gentile woman who she refers to as Mémé. Kofman’s response to her father’s deportation and her recollection of it is particularly grounded in the body, specifically in her consumption and expulsion of food: she experiences involuntary projectile vomiting concurrently with the trauma, and in her father’s absence, regiments the kashrut regulations he instilled in the family by initially refusing to eat anything non-kosher. This cycle of vomiting and then starving ends with what Brangwen Stone terms ‘Mémé’s culinary colonisation’ of young Sarah’s body: she finally accepts her meals of horse meat in butter, a coerced repudiation of her Jewishness and her own mother, with whom she experiences a difficult and violent reconciliation after the war.2 She has assimilated the forbidden diet of ‘other’ - the gentile - into herself.

A similar cycle of oscillation between denial and expulsion as a reaffirmation of the self - or inability thereof - is documented in Myriam Anissimov’s equally autobiographical Sa majesté la mort (no English translation exists, save for an extract I translated for The Isis back in 2021). Despite her Uncle Israël and Aunt Fraye’s first-hand survival of starvation in the concentration camps, and subsequent inability to control their insatiable appetites, young Myriam cannot bring herself to eat at all, let alone bountifully as her mother would have wanted. At one point, her mother’s friend coos over her delightfully chubby baby sister, before turning to Myriam and remarking ‘Comme elle est maigre ! Ma parole, on dirait qu’elle sort d’Auschwitz.’ (How scrawny she is! My word, you’d think she’d just stepped out of Auschwitz.) For the family’s immediate community, food is the currency of survival; to deny it, even in Myriam’s state of survivor’s guilt and transgenerational trauma which leads her indirectly to mimic the starvation of her relatives, is a gross offence. For Ellen Fine, this constitutes ‘[carrying] the accusations of the 'other' into their private worlds, and come to be victims - and oppressors - of themselves.’3 In other words, and contrary to Kofman, her own body became colonised by the act of not eating.

In a culture where, on the contrary, thinness carries certain currency and capital, it is hard to imagine social stigma for eating very little. As someone who has experienced the opposite - the social stigma for being unable to hide that I ate, because it would immediately show on my physical form - I may be speaking out of turn, but it feels as if the appeal for a lot of people with anorexia is the sensation that the self and other blend into one as the body physically shrinks and what was once there becomes negative space, while simultaneously setting the self apart from the unwanted foreign object that food constitutes to them. You can have it both ways, until you’re in too deep and always shivering and have unbearable acid reflux. The books got me thinking, as someone with a similar family history, that it feels like an insult to squander the virtually unlimited supply of food at my disposal: we have an old adage that comes up again and again when my we go out for dinner with my grandpa (whose cousins perished in the camps) that ‘a Jacoby never turns down dessert.’ My youngest great-great-aunt was the sole survivor of the war in her immediate family after hiding in a basement and exclusively eating tulip bulbs, while I am plagued by the mental addition required to work out the calorific value of two sushi rolls.

I am, nonetheless, a woman who likes to eat. I have written before about how I have a funny relationship to food. I do not restrict my diet per se, but I seem to have no real middle ground between getting to 3pm and conveniently ‘forgetting’ that I haven’t eaten breakfast, and gorging myself to the point of discomfort because occupying my mouth with flavour and texture is a rich source of dopamine. If I am left to my own devices, the way I act around food is entirely contingent on what is in my immediate surroundings: make it scarce, and I will easily go without; put it in my eye-line and an absent-minded hand will shovel whatever it is into my system with little regard for the content or quantity. Circumstance and environment take over with an almost automatic quality, to the point that the boundary between what is inside my body and what is outside becomes blurry as I forget what or how much I am consuming - I lose a sense of self and become ‘other’. I spent a summer between year eight and year nine permanently fucking up my metabolism and my digestive system by quite happily eating two nectarines that I would find in the fruit bowl as my breakfast/lunch, before having dinner placed in front of me by my parents, and doing this religiously every day for six weeks - I say religiously, but it just sort of happened to me, and I let it. When my mum interrogated me incredulously about whether I had been skipping meals, I said no, because it wasn’t my intention. Nevertheless, I wouldn’t have said no to the allure of not eating. Of deliberately becoming thinner. Eating food, or not eating food, feels like something so beyond my control that I need someone to take the wheel for me.

And that is exactly what I have done, for better or for worse. My parents were loyal stewards of my diet for my whole childhood, broadly healthy and successful until I was seventeen and we went on a whole-family health drive - gym five days a week, industrial quantities of crème fraîche and ladyfingers as a ‘sweet treat,’ going to bed hungry. I don’t blame them for it whatsoever, as all four of us were ravenous and miserable and overdoing it, but clinging onto the frankly alarming rate of weight loss that we’d been taught was a sign of moral virtue. My ex was driven crazy by the fact I weighed the same as I did when I was twelve, told me I was doing a great job, and then took my body measurements to calculate my precise body fat percentage before telling me it wouldn’t hurt to drop a few digits. He willingly, if indirectly, took my food intake from my parents and into his own hands. It would be fun, like a game - he’d reward me if I reached the figures he quoted. Reward me with what? Not ignoring me for weeks at a time, coming to see me over the summer holidays when he was back at home from university, but still not telling his parents I existed? I became gaunt and glassy-eyed from the mental torment alone. I tried to combat it by going to the gym even more.

After I got my A-level results, he came up to visit me, under the pretext of ‘needing to get away from home.’ We stayed in a hotel about twenty miles from where I live, neutral territory as far as the both of us were concerned. He had a habit of cancelling on me last minute if something better came up, and the sheer anxiety of building up to our first weekend away together, with the prospect of him sacking it off hanging over my head like a ten-ton lead weight, was so great that I nearly threw up on the train. I remember wearing a black top with elbow-length sleeves, covering the bits of my arms that I still didn’t like, and black skinny jeans. I felt silky and catlike under his touch as he pinched my sides and nothing came away. He said I was good. That I looked thinner.

Later that day he took me for dinner. I cannot overstate how depressing it is to be sat in a Pizza Hut in Birmingham Bullring and having to push a plate of soggy veggie deluxe towards a man who couldn’t give a shit whether you lived or died, because your stomach is churning so profusely you wonder if you’ll make it to the bathroom in time if you eat any more. The next day we went to a Mexican place and he bought me nachos, which ended up in the hotel room bin too. I woke up the next morning to find the guacamole on top all brown and festering. After we had an argument about his politics - I had shouted at him after he said that he didn’t see everyone as inherently equal and deserving of liberation movements like Black Lives Matter, and that one day I would grow up and see that, at which point I knew it was over, it had to be - I remember looking at the fetid avocado mulch and felt an indistinguishable revulsion for them as for what I’d done. How had I let it get to that point? When it ended, he told me the best part of our relationship was that he could ‘help me become more than I was.’ But being older and wiser and fuller now, it all feels like it was just an exercise in breaking me down until I was pathetic and entirely at his every whim. Becoming ‘more than I was’ by being made less; sculpted in his image, until I had no desire to eat, no desire to be, no desire except him, until I was nothing.

Now my partner Sam cooks for me. For the first time in my life, I am not tired all the time and can last the whole day without a two hour nap; I can get up and go running early in the morning; I have started writing and creating again, and things seem to have more of an inherent point to them, including being alive. I cannot, in all seriousness, stomach the idea that I was healthier before just because I was thinner - the only way I ever managed to dig down to a BMI solidly in the ‘normal’ range was by subjecting myself to a situation that I still have nightmares about seven years later. The portrait of the girl from before is almost unrecognisable, save for the one fundamental fact that I have simply passed-the-parcel with my own eating habits into the hands of a man who wants me to be full, who wants me to desire the world. Would I starve myself again if it wasn’t for him, unintentionally or otherwise? It’s difficult to say.

I do think there is something inherently sexy about liking food, being voracious about it. When we think about food and the erotic, aphrodisiacs often take centre stage - oysters, chocolate, spice - but the act of eating over the actual content, of bringing ‘the other into the self,’ of desiring something inside you, is such a key avenue of sexuality. What else would explain the popularity of mukbangs, or feeding kinks and vore? It is something that struck me about Melissa Broder’s Milk Fed. Miriam, the fat Orthodox Jewish girl who is the object of anorexic narrator Rachel's adoration, is alluring not in spite of, but because of, her fatness and her appetite: she practically force-feeds Rachel frozen yogurt, Chinese food, challah, and Rachel falls into an infatuation after being starved of affection for most of her life. The love and warmth of the family around Miriam, which Rachel lacks from her own abusive mother, is all the more fulfilling of Rachel’s deepest unmet needs, and goes hand in hand with the abundance of food in the family home and the fact that they own a frozen yogurt shop. Feeding is their business. However, in an explosive scene towards the end of the book, Rachel cannot help but argue with Miriam’s staunchly Zionist family about the Nakba and Israel’s crimes against humanity. We realise that while Miriam has the relationship with food and her mother that Rachel lacks, at the core of both young women’s situations is a yearning for nurture, a desire for a safe place that nourishes, but is purely illusory in its promises of security - for Miriam and her family, this aspirational space is Israel, but for Rachel, it is her eating disorder.* What is really jarring, however, is the disjunction between Rachel’s intense sexual attraction to Miriam’s fatness, and her own all-consuming fixation on staying thin and maintaining control - it is confirmation that the grip it has on her psyche and body comes from a place much more sinister than a simplistic wish to be attractive. It negotiates this dialectic so deftly that I think far more people would understand the potential aetiologies and motivations of disordered eating if they read it.

Like Rachel in Milk Fed, Broder’s more autofictional voice in her latest novel Death Valley is more than complimentary about the curvy woman who works in the Best Western where she is staying, and I can’t help thinking that Broder herself has a thing for us. I feel a sense of kinship with her over this. I see women in the street who have that pronounced pouch of fat in their lower abdomen and find it so beautiful. But when my arm grazes my own pouch of stomach fat, or I catch a glimpse of my lack of jawline in a shop window, I feel a disgust so deep-set that I then feel another wave of disgust at myself for being so vain and afraid of finding fatness in myself.

While overly glib and simplistic, the idea of body dysmorphia and disordered eating solely as a product of fatphobia is somewhat compelling - especially when I see fatspo Twitter raise its ugly head - but I think we have to be precise about it. The complexity of it is so evident in Milk Fed, but also in the discourse that was done to death when Taylor Swift released her music video for ‘Anti-Hero,’ where she steps on a scale and the word FAT appears instead of a number. It is undeniably different when it is the richest and most celebrated pop star of our era, who is 5’11 and willowy and beautiful, and who (more cynically) has money to make off the insecurities of her young female fans. However, for many of said young female fans, it will be about the fear of how fat women are treated. For some it will be about the wish to disappear. For some, like Rachel, it will be about internalising the abuse from their mother and searching for a place where they feel safe and in control, regardless of their love for and attraction to fat women. For others, it will be because, years ago, their not-quite-boyfriend told them they had real potential to be pretty if they weighed less than they did when they were twelve and also changed everything about themselves. It’s fatphobia, yes - but it’s a yes, and.

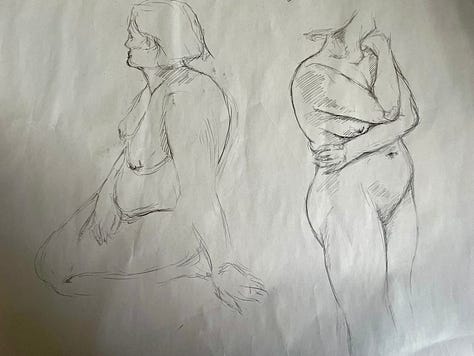

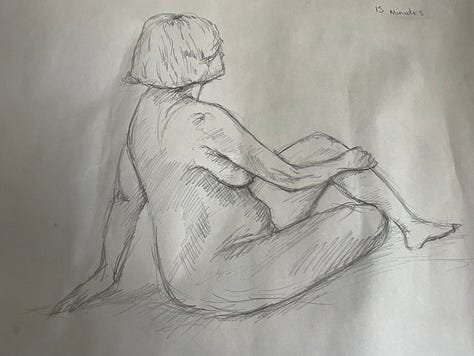

It’s 7pm and I’m at a life drawing class in central Melbourne. I’m sat by the exit and the room is full and sweltering - I’m one of about three people who hasn’t come with someone and I can’t bring myself to strike up conversation. As if to knock me off balance after a week of dipping into my past while writing this, in a space where I feel so comfortable - visual art was my first love, before writing, before language - there’s a man in the corner with a prominent furrowed brow who looks like an uncanny valley version of my ex. He isn’t talking to anyone either, and he has started drawing even though the model hasn’t arrived yet. There are three girls to the right of me, one dressed like a cottagecore Pinterest board with wide rounded glasses that she pushes up the bridge of her dainty little nose; the next in a seventies-style getup with a long skirt and boots reminiscent of Stevie Nicks; the one on the end sporting wine-black lipstick, matching hair and a sweater vest. There’s someone on the other side with blue highlights and denim shorts who walks in sullenly, before sitting down next to an older lady and starting to open up, wry smiles and then laughter. Where do I fit here? I may as well be invisible, but then the cottagecore girl smiles at me: though we don’t talk, I feel grateful that someone has seen me, and grateful that being seen no longer terrifies me as much. The model walks in (I’m thankful it’s not an old man with a wrinkly ballsack like the last time I did a workshop like this - no body shaming, just very difficult to draw in a dignified way) and she takes her robe off in one swift movement. Some of her features are just like mine, and between the moments of purely logistic neutrality in considering how to move the pencil around the page to sculpt the flesh, to denote muscles and fat and movement and tension, I find it very beautiful. It would be a shame not to. Isn’t the body a miracle?

*I don’t want to touch too much on the themes of Zionism, insecurity, paranoia and mother issues in the book, as I have another essay cooking on this and Ari Aster’s film Beau is Afraid.

Robson, Kathryn, ‘Bodily Detours: Sarah Kofman’s Narratives of Childhood Trauma’, The Modern Language Review, 99.3 (2004), 608 <https://doi.org/10.2307/3738990>

Stone, Brangwen, ‘Food, Culture, and Identity in Vittorini’s Conversation in Sicily and Kofman’s Rue Ordener, Rue Labat’, CLCWeb: Comparative Literature and Culture, 15.1 (2013) <https://doi.org/10.7771/1481-4374.1997>

Fine, Ellen S., ‘The Search for Identity in Post-Holocaust French Literature: The Works of Myriam Anissimov’, Holocaust and Genocide Studies, 5.2 (1990), 205–16

Your writing is incredible! Loved this :)