I have started Russian lessons. We’re still on the basics, which I already know as Russian has come in and out of my life when I have needed it: when I was eight, a girl from Moscow joined our class, and I wrote her a welcome card by copying off Babelfish; I taught myself the Cyrillic alphabet aged fifteen because I wanted a cool party trick; I studied it at seventeen and twenty-one and twenty-three. I never got very far, because I had to focus on the languages I studied for my degree (French, my first love, and Spanish, which I never really took to and only chose because my mother begged me not to go to Russia on my compulsory year abroad). This time I’m promising myself to make a commitment to Russian, to make a real friend of it. It is week two and we have just learned Кто это? (who is this?) and Что это (what is this?). The homework activity tells me to write a short dialogue for each picture. The first one is a man and woman waving at a computer screen. I write:

— Привет бабушка! Привет дедушка! Как у вас дела? (Hi grandma! Hi grandpa! How are you both?)

— Здравствуйте! Спасибо, отлично. Кто это? (Hello! Excellent, thank you. Who is this?)

— Это моя новая жена, Лена. (This is my new wife, Lena.)

— Приятно познакомиться. (Very nice to meet you).

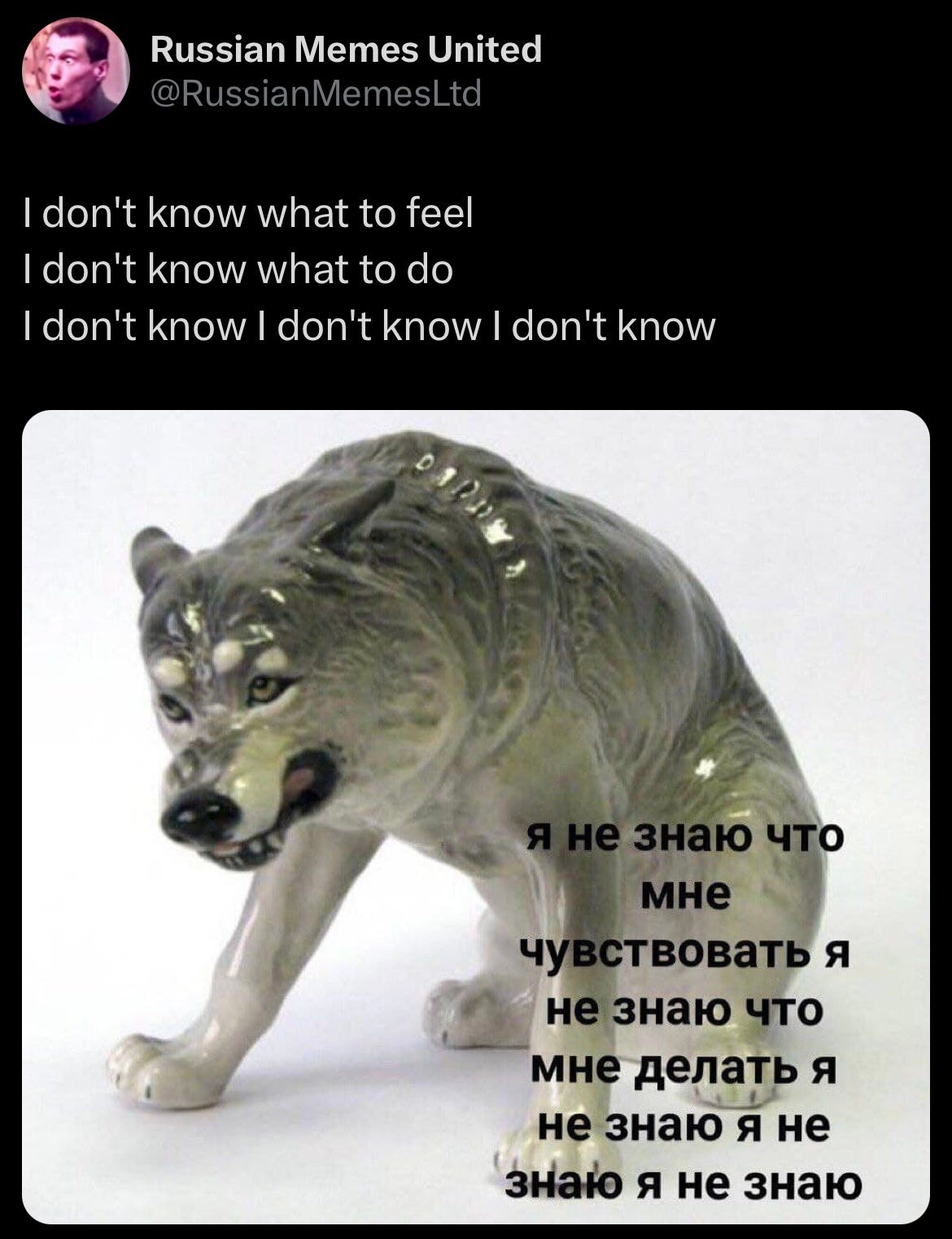

I wanted to come up with a backstory for the Russian man and his new wife Lena, but I found that my language stopped there. I don’t have the words to describe their lore in a way that felt right or empowering – relying on a dictionary makes me feel helpless and inauthentic, as if I depend on someone else to put words in my mouth instead of really feeling them myself. My mother tells me that when this happened in my infant years, it would frustrate me so badly I would throw an almighty tantrum to communicate, because I didn’t have the English to do so yet. I wanted the grandmother and grandfather to be unimpressed. The man had married Lena on a whim; they had met three months ago, unceremoniously ending his previous relationship, or maybe even not ending it at all, treating her like a fucking idiot while she knew deep in her gut that he was gone. How much of that can be gleaned from my dialogue? Maybe the кто это and the новая жена give it away, the sarcastic приятно познакомиться, the surprise of it all, the wariness. The indignity. The betrayal. I don’t know the Russian for that.

Ironically, I am dipping in and out of The Idiot by Elif Batuman when I am not too upset to concentrate. Russian as a language, its literature, and language in general take on a central role for the protagonist-narrator, Selin, who has just arrived at Harvard. She, too, makes sense of things through the stories she has to read for her Russian class: a woman pines for a man who has fled suddenly to Novosibirsk, while she pines for a man who maintains enough emotional distance between them that he may as well be in Siberia too. They exchange emails, mediating their feelings through heavy intellectualisation and musings on linguistics, which actually leads to more miscommunication than anything. Maybe if they had stuck to the limits of their new language, it would not be so painfully drawn out. The mind games fall away; the honest truth is all that is left. You cannot circle the point if you’re not hopelessly articulate.

Between classes, I watch Bridget Jones’ Baby. I break into voiceless sobs at the part where she reaches for Mark Darcy and asks what will happen if the baby is not his, and he says he will love it anyway, just like he loves her. I try somatic yoga for emotional release and it does not work. My lower back feels better but I pull a muscle in my side. I try to cancel our phone bills that both go through my bank account and I have to explain my situation to the Vodafone 24/7 chat assistant. I feel like I am holding her hostage: she asks me how I am, I say okay, and she says ‘Vodafone is happy to hear of your wellbeing :)’ before I tell her we have broken up so no I cannot get him on the chat to verify his identity right now. I wake up alone. I go to sleep alone. I brush my teeth alone. But I only feel as alone as I felt for the last three months.

Every time I think about being back there I feel my heart throwing itself at the wall of my chest and I have to take my medication. I probably don't give myself enough credit for the fact I have just had possibly some of the most traumatic few months of my life, completely isolated in a country ten thousand miles from my home, but I am struggling to see the utility of it all. What is this all for? It's not noble. It's not brave. I'm just responding to the cards I have been dealt, for some twisted and cruel reason, and it is almost too much to bear. When I was seventeen, yearning for a man who hit me so hard I couldn’t sit down and then ignored me for weeks on end, I thought it was all awfully glamorous and that I would one day have a story to tell. If nothing else, I was living the story; I was feeling it, fully actualised and front-and-centre instead of a supporting role in my own life. This — this is just a special kind of hell. There’s no grand narrative I can spin it into, no work of art I can birth from the rubble, to feel like my suffering will all be worth something, because it feels embarrassing and shameful to have been treated like this, to have allowed it to get to this point. It is just damage. I feel like damaged goods.

We’re progressing in Russian. We have four hours per week, plus at least five homework tasks, which is strange to say at nearly twenty-six years old, but I watched a documentary about preventing dementia and apparently learning a new skill is good for the neural pathways, so I’ve been going at it obsessively. It has been nine weeks since I started. I have gone above and beyond and taught myself to write in cursive, which isn’t required yet, but I find printing letters difficult as I write in cursive in English, so now I’ve got the hang of it it is much easier for me. The letters transmute in a way that is both pleasing and infuriating to me: the letter Т becomes a lower-case m; a Д looks like a g. To make things more confusing, Б in lower-case looks sort of like a Latin-script d. Nothing is as it seems on the surface, in the glossy textbooks and the literature and the news. The other reason I learned cursive now is that I didn’t want to become so set in my ways down the line that it would be difficult for me to pick up. I like to be prepared for the difficulty, to get it over with. I bargained with myself that if I could speed run the five stages of grief, I could bury it or burn it or otherwise cleanse myself entirely. I got stuck on anger, then denial, and now I feel numb. Maybe it is working.

In the beginning of learning a language, there is a certain self-narrative you practice within the limits of what you can say. Talking about yourself is the bedrock that you build on, so you become intimately familiar with a version of yourself that is circumscribed by your poor linguistic ability. Sometimes this means lying for the sake of ease. I used to do this a lot when I began learning Spanish. In my first year oral exam, I was asked if I’d ever been to the top of the Eiffel Tower; I said no, and the only reason I could articulate with my nerves and shoddy language was not ‘I am scared of heights,’ but ‘tall buildings scare me.’ I butchered the construction and said ‘porque los edificios altos me dan mierda.’1 Nevertheless, I find it very hard to do, because I cannot lie through my teeth. I cannot lie at all. I would rather stumble through a stupid-sounding, grammatically incorrect but factually accurate sentence, grasping at straws, leaning on others for help, than a blatant untruth — which makes it all the more earth-shattering that others can do it without it eating them alive.

We have just learned the prepositional case, and we’re all getting pretty good at it. The case system is something I haven’t come across before — I’ve never studied German or Latin — but it makes a lot of inherent sense to me. Nothing is superfluous, and everything fits together so nicely. We haven’t covered opinions or emotions yet, and adjectives are difficult, so I’m not touching them until I fully understand how to use them. Anything subjective is jettisoned. In Russian, my current self-narrative is marked by the prepositional case; where I am, where I was, where I will be, objectively:

Меня зовут Милли. Мне 25 лет. Моя день рождения зимой, в феврале. Я живу в Ковентри, в Англии, но в прошлом году я жила в Австралии. В Австралии, я часто плавала в море, но Ковентри — очень далеко от море. У меня есть мама, папа и брат. Моя мама — учитель. Мой папа — биолог. Я говорю свободно по-французики, неплохо по-испански и по-китайски, а сейчас я изучаю русский язык.

My name is Millie. I am 25 years old. My birthday is in winter, in February. I live in Coventry, in England, but last year I lived in Australia. In Australia, I often swam in the sea, but Coventry is very far from the sea. I have a mum, a dad and a brother. My mum is a teacher. My dad is a biologist. I speak fluent French, okay Spanish and Chinese, and now I study Russian.

It takes me a good ten minutes to type those five lines, which feels very slow to me as I am a 75-words-per-minute touch-typer in English. You have to be far more deliberate with a keyboard in a script that isn’t your own. It also allows you to process exactly what you are writing about yourself. I swam in the sea maybe three times in Australia. I haven’t spoken Spanish or Chinese in over three years. I do have a mother, a father, a brother, but there’s a big person-shaped hole that I go to reach for each time, knowing it has to stay there, knowing it has to remain between the lines. Knowing I can’t go back, not now, likely not ever.

We’ve learned the verb любить (pronounced lyubit’), ‘to love’, but not the construction for ‘to like.’ Things I have recently learned that I love include: walking in the park; watching films on a Sunday; chess; old cities like Veliky Novgorod, which I have never been to. It’s okay. I don’t think ‘to like’ is in my vocabulary anyway — I have never been lukewarm about anything. I go on a date with a man who is leaving soon to go back home, twelve thousand miles away, to a country I have been to and did love. I am so consumed with guilt and desire that he occupies most of my waking moments, even though we have only just met. He pays for all of my drinks. He speaks to me softly, doesn’t make fun of me as a form of flirting (which I hate), uses phrases I have to Google later on in an accent I cannot get out of my head. new zealand yeah nah. new zealand nah yeah. new zealand ‘crack up.’ He strokes my shoulder and the small of my back, deliberately and of his own volition. He is decisive in a way I am not. I have nothing to be guilty about — the way I have been treated is exponentially worse than any foolish impulse I could act on now — but I’m burning from the inside out, and I cannot distinguish whether it is out of shame or want, or an overwhelming mix of the two, feeding each other in an endless feedback loop. All I am programmed to know is любить, любить, любить, over and over again.

I have my first exam next week, so our teacher asks us to write a practice composition. It’s only 120 words, so I send her my stock paragraph, carefully rehearsed and regurgitated in cursive. She sends back her points for improvement: Can you write about what you like to do in your free time? Could you tell me about your home? I don’t know anymore. I don’t think I will know for a while.

‘tall buildings give me shit’ (it should be ‘los edificios altos me dan miedo’)

This is devastatingly earnest and heartfelt; I’m grateful to have a chance to read. I’m sorry that you’re going through grief and loss; losing that one person is the most painful, earth-shattering life changes to try to process. The heavy void of grief, like having a human-sized hole dug out from inside the chest, the abyss of missing a loved one and yet to keep going, searching for them through the lens of tear-stained memories, you render this tragic experience with tender clarity and accuracy. It seems so cruel to me that we have to go through the loss of a beloved in the end. So many of your sentences rang true. I like the part about not feeling in half measures, but rather with an intensity and fullness. I agree about not being any good with lies or mockery; the part you wrote: “I cannot lie at all. I would rather stumble through a stupid-sounding, grammatically incorrect but factually accurate sentence, grasping at straws, leaning on others for help, than a blatant untruth — which makes it all the more earth-shattering that others can do it without it eating them alive.” Yes, I agree. Sincerity can feel like my near-fatal flaw, but also in these days of lies and distrust, I think sincerity is a good quality, a rebellion against the postmodern status quo of apathy and irony that’s often been weaponized against us. I have to add that I think you are not damaged goods, I promise (I’m quite familiar with that damaged feeling too.) The fact that you’re still writing, publishing, learning languages: that means your inherent self is strong, invaluable, and worth listening to by reading your brilliant, sincere writing. Thank you for writing and sharing your experience. Please know that I do appreciate, respect, and value your ongoing project to write and to speak the truth. That’s no small task, and it makes a difference for other people who have gone through similar losses in the past. Keep going with your writing art; keep up the good fight. You’re a good person and an extraordinarily gifted, beautiful writer.

I'm so sorry, Millie. Jessica's comment captures everything I want to say far more eloquently than I can, so I'll just say this: thank you for writing this piece. So much writing feels excessively cold and detached right now, and I always appreciate how yours never sacrifices sincerity and feeling.